PBS 6 of X: Introducing CSS

We have now learned enough HTML to encode basic page content, marking things as headings, paragraphs, lists, etc.. We have completely ignored the look of our pages so far – relying on our browsers’ default styles. The default styles, it’s fair to say, are pretty darn ugly, which is why almost every page on the web has at least some basic styling applied to override these defaults.

In the bad old days, HTML pages were styled by adding attributes directly into the HTML tags. This was very time-consuming, and it greatly reduced the reusability of the HTML markup. Those attributes still exist in the HTML spec, but we have completely ignored them, and will continue to do so for the entire series. This is not the bad old days, so we now have access to a much better solution – Cascading Style Sheets, or CSS.

Matching Podcast Episode 420

Listen Along: Chit Chat Across the Pond Episode 420

You can also Download the MP3

CSS Overview

In a CSS-enabled web browser, every HTML tag in a page has a collection of style properties associated with it. Each of these properties has a default value. If no styling is applied to a page, those default values are used. CSS (and JavaScript) can be used to alter these properties, and hence, alter the appearance of pages.

CSS is currently at version 3. Each new version has added new properties and selectors (more on those later) to CSS. So far, the versions have all been additive – that is to say, CSS 3 is a super-set of CSS 2 which is a super-set of CSS 1. In this series we are assuming modern browsers and HTML 5 support; so we will also assume CSS 3 support.

The fundamental atom of a CSS style sheet is the style declaration, which is just a name-value pair. The name is a style property name, and the value is the value that should be set for that property. The CSS specification defines the list of existing property names, what values they can accept, and what effect the values will have on the presentation of page. The individual declarations are very simplistic – e.g. color: red;, but when combined, they become very powerful.

Style declarations are applied to HTML tags using so-called selectors – these range from the simple to the downright complex. A simple selector would be p, which selects all paragraph tags, while p a[target="_blank"], ul > li selects all links with a target of _blank within paragraphs and all list elements whose parent is an unordered list.

Finally, the reason the word cascading is in CSS’s name is that style attributes are inherited from parent tags, or, in other words, they cascade down through the document. If you specify that the text in all paragraphs should be blue, then the text within an emphasised region within a paragraph will inherit that blueness from its parent paragraph.

Notice that the style for each HTML tag will be the result of combining style information from many sources – the styles of the containing tags, and, potentially, style declarations from multiple selectors. It is inevitable that there will be conflicts – if all paragraphs should be blue, but all emphasised text should be dark grey, what colour should emphasised text within a paragraph be? This kind of conflict resolution is handled by a complex algorithm which assigns each of the specified values for a key a specificity, and the value with the highest specificity wins!

Understanding specificity is the key to mastering CSS. So it’s a term that will come up many times in the next few instalments. The full specificity hierarchy is very complex, so we’re going to build up our understanding of that hierarchy incrementally.

Adding CSS to a HTML Document

There are three distinct ways to incorporate CSS into a HTML document. They all have their valid uses, but, from a best-practices point of view, there is a distinct hierarchy.

Import an External Stylesheet

This is by far the preferred means of adding CSS to an HTML document. It allows the same CSS declarations to be applied to many documents. It allows browsers to cache the CSS data. It also involves the minimal amount of alterations to the HTML document.

To import an external style sheet, use the <link> tag within the <head> section of the document as follows:

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="URL_TO_STYLE_SHEET" />

Note that the link tag is void, so you should never write a closing link tag.

Define an Internal Style Sheet

If your entire project consists of just one HTML file, it sometimes makes sense to include all the styles within that one HTML file. If you find yourself copying-and-pasting an internal style sheet between multiple files, you really should be using an external style sheet instead!

It often also makes sense to use an internal style sheet in conjunction with an external one. Styles common to all documents in a project can be defined in the external style sheet, but styles that apply to just one page can be defined internally.

Internal style sheets should be defined within a <style> tag within the <head> tag.

The style Attribute

HTML tags can specify CSS declarations to be applied to themselves using the style attribute. Use of this approach should be absolutely minimised because it undoes most of the advantages CSS brings to the table. However, it can be useful from time to time because CSS declarations specified via the style attribute have the highest possible specificity; so they will trump all conflicting declarations in both imported external style sheets and the internal style sheet.

The following example shows a style attribute on an image tag used to force the border to always be zero pixels, regardless of what is specified in any applicable external or internal style sheets:

<img src="img.jpg" alt="an image" style="border-width: 0px;" />

Basic CSS Syntax

The two main components of the CSS syntax are style declarations and selectors. Selectors are used to map a collection of declarations to a collection of HTML tags. The style attribute is a special case; it does not allow selectors and simply expects a list of style declarations.

At the highest level, CSS syntax can be summarised as follows:

/* THIS IS A CSS COMMENT */

CSS_SELECTOR{

CSS_DECLARATION;

...

CSS_DECLARATION;

}

/* The same declarations can be applied to multiple selectors */

CSS_SELECTOR1, CSS_SELECTOR2, ... {

CSS_DECLARATION;

...

CSS_DECLARATION;

}

CSS Style Declarations

As previous stated, each CSS style declaration is a name-value pair, where the name is a CSS property name as defined in the CSS specification, and the value is an appropriate value for the given property, again, as defined in the CSS specification.

The basic form of a CSS declaration is as follows:

CSS_PROPERTY_NAME: CSS_PROPERTY_VALUE;

You can get a full list of all valid CSS property names, the values they expect, and the versions of CSS they were introduced with at this link. Consider that link a useful reference, not a tutorial! We will look at many of the most commonly used and important CSS properties over the next few instalments.

CSS Selectors

The CSS selector syntax is extensive and complicated, and has become more so with every new version of CSS. Rather than confusing everyone with a detailed list of all supported selectors in this CSS introduction, we’ll instead build up our understanding of selectors slowly over the next few instalments. For now, we’ll start very simple – a CSS selector is a HTML tag name without the surrounding angle brackets, or the special character * to apply a declaration to all tags.

A First Approximation of Specificity

This is a highly simplified description of specificity that only applies to the simplified world where CSS selectors are just tag names or the symbol *. As we learn about more selectors, we’ll also develop a more detailed understanding of specificity as well.

- Style declarations contained in style attributes have the highest possible specificity

- Style declarations with the selector

*, properties inherited from containing tags, and default property values have the lowest possible specificity – zero - If there are two declarations for the same property on the same tag with the same specificity, the one declared last wins – that is to say, the one declared the furthest from the start of the document wins.

Basic Text Formatting With CSS

What follows is just a sampling of some of the most commonly use text-formatting CSS properties.

Text Colour

The CSS property for specifying text colour is simply color (spelled the American way). The value for this property can be expressed in one of a number of supported formats:

- Colour Names

- The CSS specification includes a large list of named colours. All the obvious ones like

Red,Green,Blue,Yellow,Purple,Black,White, etc. are there, but the list is much more extensive, and includes more unusual colours likeCornflowerBlueandDarkOliveGreen. You can find a full list of all the supported names with samples of the colours here. - HTML Colour Codes (HEX)

- In HTML, colours are specified as three HEX values between 0 and 255, or more specifically, between

00andFF, representing the red, green, and blue values for the colour. These same values can be used in CSS, and, like in HTML, they must be prefixed with the#character. For example, pure red is#FF0000. - RGB (Red, Green, Blue)

- The RGB components can be given as three decimal values between 0 and 255 using the following format:

- RGB with Alpha (Opacity) AKA RGBA

- An RGBA colour is basically the same as an RGB colour, but with a fourth parameter, the opacity, which should be a value between 0 and 1 where

0is fully transparent, and1is fully opaque. RGBA values are specified as follows: - HSL (Hue, Saturation & Lightness)

- Modern browsers also support the HSL colour representation – like RGB this involves three parameters, but in this case the first parameter is the hue, given as a value between 0 and 360, representing the position of the colour on the colour wheel in degrees. The second parameter is the saturation, given as a percentage, and the third is a lightness, also given as a percentage. The format for specifying an HSL colour is as follows:

- HSL with Alpha AKA HSLA

- The same as a HSL value, but with an opacity parameter added, again, represented as a value between 0 and 1, like with RGBA. The format is as follows:

rgb(RED_VALUE, GREEN_VALUE, BLUE_VALUE)

For example, pure red would be rgb(255, 0, 0).

rgba(RED_VALUE, GREEN_VALUE, BLUE_VALUE, ALPHA_VALUE)

For example, semitransparent pure red would be rgba(255, 0, 0, 0.5).

hsl(HUE_IN_DEGREES, SATURATION_VALUE%, LIGHTNESS_VALUE)

hsla(HUE_IN_DEGREES, SATURATION_VALUE%, LIGHTNESS_VALUE, ALPHA_VALUE)

The following three definitions all set the colour to the same shade of red:

color: Crimson;

color: #DC143C;

color: rgb(220, 20, 60);

Fonts

The font-family CSS property is used to specify the font to use when rendering text. This property does not take a single value, but a comma-separated list of fonts, or font groups to use, listed in order of preference. Because you can’t assume that every one who browses your web page has your favourite font installed, it’s good practice to start with one or more very specific fonts, the ones you really want, then to include a more general group of fonts similar to the one you really want, and finally a very generic font group like serif, sans-serif, or monospace.

For those of you not familiar with typographic terminology, a serif font is a variable-width font that has little appendages on the edges of many of the letters, e.g. on the ends of the bar at the top of an upper-case T. The best known example of a serif font is probably Times New Roman. A sans serif font is a variable width font without the little appendages. The best known sans-serif font is probably Arial. A variable width font is one where different letters have different widths. A fixed-width font, or monospace font is one where each letter is rendered at the same width. The most common example of a monospace font is probably Courier New.

Below are some example best-practice font-family declarations:

font-family: "Times New Roman", Times, serif;

font-family: Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif; /* My preference */

font-family: Verdana, Geneva, sans-serif;

font-family: "Courier New", Courier, monospace;

W3 Schools has a nice list of common web-safe font-family declarations.

Font Size

The size that text should be rendered at is controlled with the font-size CSS property. This property can specify sizes in a large range of units, both explicitly, and relatively.

- Named Absolute Sizes

- There are named sizes, ranging from

xx-smalltomediumtoxx-large. The default size for text in regular tags ismedium. - Named Relative Sizes

- There are two named relative sizes, each making the text one unit bigger or smaller than font size of the tag’s parent tag (

mediumtolarge,largetox-large,mediumtosmall,smalltox-small, etc.). The two named relative sizes aresmallerandlarger. - Absolute size in Points

- An absolute size in points can be specified as a number with

ptappended to it, e.g. a 12 point font would be written as12pt. - Absolute size in Pixels

- An absolute size in pixels can be specified as a number with

pxappended to it, e.g. a 10 pixel font would be written as10px. - Relative Size as a Percentage

- The font-size for an element can be specified as a percentage of the size of the font in the tag’s parent tag by specifying it as a number between 0 and 100 with the `%` symbol appended. E.g. to make the font half the size of the parent tag’s font, specify the size as

50%.

Italics & Bold

The following examples show how to enable and disable bold and italics:

font-style: italic; /* enable italics */

font-style: normal; /* disable italics */

font-weight: bold; /* enable bold */

font-weight: normal; /* disable bold */

Underline, Overline, & Strikethrough

The text-decoration CSS property can be used to add a line under, over, or through text.

text-decoration: underline; /* underline text */

text-decoration: overline; /* overline text */

text-decoration: line-through; /* strikethrough */

text-decoration: none; /* no line (default) */

Text Alignment

The alignment of text is controlled by the text-align CSS property. Valid values are left, right, center, and justify.

The default alignment depends on the active text direction. If the text direction is left-to-right, the default alignment is left, and if the text direction is right-to-left, the default alignment is right.

Note that the text direction can be controlled with the direction CSS property. Valid values for this property are ltr for left to right, and rtl for right to left. In turn, the default value for the CSS direction property is determined by the page’s language. This can be specified by the web server using an HTTP header, or by the page itself using a <meta> tag within the header something like:

<meta http-equiv="Content-Language" content="en-UK" />

Finally, if there is no language using either the HTTP header, or the meta tag, the browser will assume a default based on the locale of the operating system it is running on.

In reality, what all this means is that, in the western world, if we don’t specify either an explicit language, or an explicit text direction, the default direction will be left-to-right, and the default text alignment will be left.

Case Transformations

The text-transform CSS property can be used to alter the case of the text within an HTML tag. This can be especially useful for headings.

text-transform: capitalize; /* upper-case the first letter of each word */

text-transform: lowercase; /* convert to all lowercase */

text-transform: uppercase; /* covert to all caps */

text-transform: none; /* leave the case as-is (default) */

A Worked Example

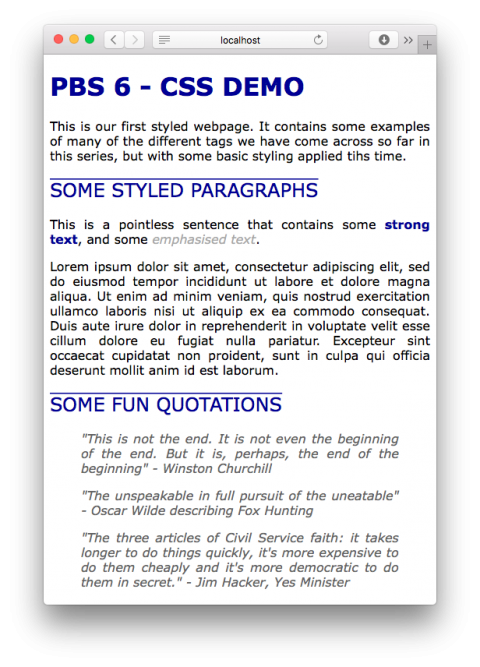

As an example, I have created a web page that makes use of many of the HTML tags we’ve learned about so far, and imported an external CSS stylesheet to style those tags. You can download a zip file containing both files here or here on GitHub. The two files in the zip should be extracted to a folder called pbs6 in your web server’s document root folder.

The contents of both files are shown below:

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<title>PBS 6 - CSS Demo</title>

<!-- Import the style sheet (using a relative URL) -->

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="style.css" />

</head>

<body>

<h1>PBS 6 - CSS Demo</h1>

<p>This is our first styled webpage. It contains some examples of many of the

different tags we have come across so far in this series, but with some basic

styling applied tihs time.</p>

<h2>Some Styled Paragraphs</h2>

<p>This is a pointless sentence that contains some <strong>strong text</strong>,

and some <em>emphasised text</em>.</p>

<p>Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod

tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam,

quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo

consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum

dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident,

sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.</p>

<h2>Some Fun Quotations</h2>

<blockquote>

"This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is,

perhaps, the end of the beginning" - Winston Churchill

</blockquote>

<blockquote>

"The unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable" - Oscar Wilde describing

Fox Hunting

</blockquote>

<blockquote>

"The three articles of Civil Service faith: it takes longer to do things

quickly, it's more expensive to do them cheaply and it's more democratic to do

them in secret." - Jim Hacker, Yes Minister

</blockquote>

</body>

</html>

/*

Styles for PBS 6 worked example

*/

/* Set the default text style for the whole page */

body{

font-family: Verdana, Geneva, sans-serif;

text-align: justify;

}

/* Style headings */

h1, h2{

text-transform: uppercase;

color: #000099;

}

h2{

font-weight: normal;

text-decoration: overline;

}

/* make strong text dark blue */

strong{

color: #000099;

}

/* make emphasised text grey */

em{

color: DarkGrey;

}

/* style quotations */

blockquote{

font-style: italic;

color: rgb(100, 100, 100);

}

Once both files are saved in the appropriate folder, and your local web server is started, you should be able to see the resulting page at the URL http://localhost/pbs6/. The page should look something like:

Conclusion

This instalment is just a very basic introduction to CSS. We still have a lot more to learn! In the next instalments we’ll learn about the CSS box model, more advanced selectors, more CSS properties, and even some new HTML tags designed to facilitate easy styling. We’ll start with the box model though, because a good understanding of the box model is critical to effective styling.