PBS 29 of X: JS Prototype Revision | Glyph Icons

In this instalment we’ll continue with our twin track approach of revising JavaScript prototypes and learning about HTML forms.

We’ll start by moving our JavaScript revision out of the PBS playground, and over to NodeJS, getting you much better error reporting. Then we’ll have a look at my sample solution to the challenge from the previous instalment, and we’ll eradicate another bad smell from the prototype. We’ll come face-to-face with the implications of the fact that variables don’t contain objects, but references to objects. If you don’t bear that fact in mind, you can end up with spooky action at a distance that seems like the worst kind of black magic. The kind of bugs that baffle, mystify, and drive you nutty as squirrel poo!

We’ll then switch gears back to HTML forms, where we’ll learn about a very powerful technique for including scalable vector-based icons in your form elements. These very special icons are known as glyph icons. While rolling your own is a significant undertaking, you don’t have to, because you can use icon sets created by others. We’ll learn about glyph icons using the free and open source glyph icon set from Font Awesome.

You can download a ZIP file containing the sample solution to the previous challenge, and, the example HTML file from today’s examples here or here on GitHub.

Matching Podcast Episode 474

Listen Along: Chit Chat Across the Pond Episode 474

You can also Download the MP3

Taking Our Prototype Revision out of the PBS Playground

While doing my own homework (writing a sample solution to the challenge I set in the previous instalment) I came to the realisation that we have outgrown the PBS playground. It was designed as a temporary home in which we could learn the basics before moving into the browser proper.

The biggest shortcoming with the playground is its poor error reporting. Sure, it gives you an error message, but it can’t tell you which line within your code triggered that error. When you’re working on small tasks requiring just a few lines of code, this is not a problem, but our prototypes are hundreds of lines long now!

We absolutely need a way of testing our prototypes as we build them that will give us detailed error reporting.

By far the simplest solution is to install a command line JavaScript engine like NodeJS (Node for short). With Node installed, you can save your code to a text file with a .js file extension, and then run it with a command of the form:

node myFile.js

Node is free, open source, and cross-platform, so anyone can play along. Node is also quick and easy to install. The Node website will offer you two downloads, an LTS (Long Term Support) version, and the very latest version. The LTS version is labeled as recommended for most users, and that’s what I always install.

While Node gives us a place to run our code, it doesn’t give us a place to edit our code. You can literally use any plain-text text editor. However realistically, you’re going to want to use a programming editor with features like syntax highlighting and bracket matching. Earlier in the series I suggested the free and open source editor Atom for editing your HTML and CSS files. You can use Atom for your JavaScript files too. It will give you features like syntax highlighting, code auto-completion, and bracket matching.

So now we have a nice editor and a place to run our code. Will it just work?

Nope, but don’t worry. You just need to make two very small changes to get your code working in our new environment:

- Uncomment the namespace declaration (

var pbs = pbs ? pbs : {};) at the top of your code. This was only commented out because of the playground’s idiosyncrasies – it’s needed everywhere but in the playground. - Replace all occurrences of

pbs.saywithconsole.log. As its name suggests,pbs.say()is a feature of the PBS playground, not a standard JavaScript feature.

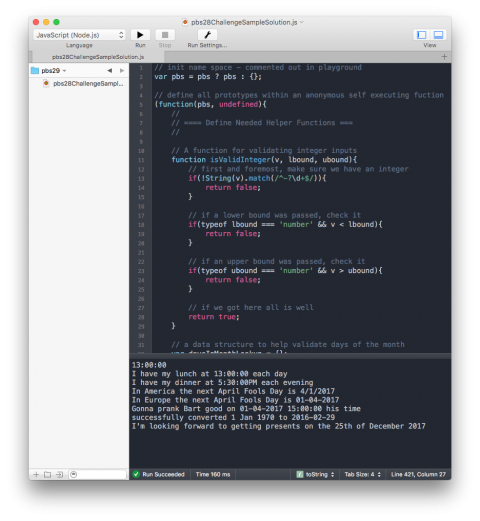

Some code editors can do much more than just editing code – they can also run it right within the editor. I recently discovered an editor like this which I’ve fallen in love with. I am now using it to do all my code samples and sample solutions for this series. It can run NodeJS code, it does syntax highlighting and bracket matching, and it even understands the code you’ve written enough to suggest auto-completions of function names etc. as you type.

The editor I’m describing is Code Runner 2. It’s only available for macOS, and it costs €14.99. It’s available directly from their website or from the MacApp Store. The Mac App Store version is limited by macOS’s sandboxing. While it can give you syntax highlighting and things like that, it can’t run NodeJS code. Thankfully, the Code Runner people have added a feature to the App Store version of their app that tells you when you hit such a limitation, and provides you with really simple instructions for converting your App Store purchase into a license key for the non-App Store version which you can download from their website. This conversion is really quick and easy, and costs nothing.

It’s obviously easier to buy direct. Then you won’t have to go through the conversion process. But if you have iTunes credit, the fact that you can use it and then convert is very useful.

Solution to PBS 28 Challenge

Below is my solution to the challenge from the previous instalment, written to run via NodeJS rather than in the PBS playground.

// init name space - commented out in playground

var pbs = pbs ? pbs : {};

// define all prototypes within an anonymous self executing function

(function(pbs, undefined){

//

// ==== Define Needed Helper Functions ===

//

// A function for validating integer inputs

function isValidInteger(v, lbound, ubound){

// first and foremost, make sure we have an integer

if(!String(v).match(/^-?\d+$/)){

return false;

}

// if a lower bound was passed, check it

if(typeof lbound === 'number' && v < lbound){

return false;

}

// if an upper bound was passed, check it

if(typeof ubound === 'number' && v > ubound){

return false;

}

// if we got here all is well

return true;

}

// a data structure to help validate days of the month

var daysInMonthLookup = {};

daysInMonthLookup[1] = 31;

daysInMonthLookup[2] = 28;

daysInMonthLookup[3] = 31;

daysInMonthLookup[4] = 30;

daysInMonthLookup[5] = 31;

daysInMonthLookup[6] = 30;

daysInMonthLookup[7] = 31;

daysInMonthLookup[8] = 31;

daysInMonthLookup[9] = 30;

daysInMonthLookup[10] = 31;

daysInMonthLookup[11] = 30;

daysInMonthLookup[12] = 31;

// helper function to validate a given combination of day, month, and year

function isValidateDMYCombo(d, m, y){

// figure out how many days are allowed in the curreny month

var numDaysInMonth = daysInMonthLookup[m];

if(m === 2){

// the month is February, so check for a leap year (assume not)

var isLeapYear = false;

if(y % 4 === 0){

// year is divisible by 4, so might be a leap year

if(y % 100 === 0){

// a century, so not a leap year unless divisible by 400

if(y % 400 === 0){

isLeapYear = true;

}

}else{

// divisible by four and not a century, so a leap year

isLeapYear = true;

}

}

// if we are a leap year, change the days to 29

if(isLeapYear){

numDaysInMonth = 29;

}

}

// return based on wheather or not the days are valid

return d <= numDaysInMonth ? true : false;

}

// helper function to convert integers to zero-padded strings

function intToPaddedString(i, len){

// take note of whethere or not the original number was negative

var isNegative = i < 0 ? true : false;

// convert the absolute value of the number to a string

var ans = String(Math.abs(i));

// add any needed padding if a sane length was provided

if(typeof len === 'number' && len > 0){

while(ans.length < len){

ans = '0' + ans;

}

}

// pre-fix the minus sign if needed

if(isNegative){

ans = '-' + ans;

}

return ans;

}

// a helper function to get the two-letter ordinal suffix for any integer

function toOrdinalString(n){

if(n === 1){

return 'st';

}

if(n === 2){

return 'nd';

}

if(n === 3){

return 'rd';

}

return 'th';

}

// a lookup table to convert month numbers into English names

var monthNameLookup = {};

monthNameLookup[1] = 'January';

monthNameLookup[2] = 'February';

monthNameLookup[3] = 'March';

monthNameLookup[4] = 'April';

monthNameLookup[5] = 'May';

monthNameLookup[6] = 'June';

monthNameLookup[7] = 'July';

monthNameLookup[8] = 'August';

monthNameLookup[9] = 'September';

monthNameLookup[10] = 'October';

monthNameLookup[11] = 'November';

monthNameLookup[12] = 'December';

//

// === Define Time protoype (Part 1) ===

//

// the constructor

pbs.Time = function(h, m, s){

// init data with default values

this._hours = 0;

this._minutes = 0;

this._seconds = 0;

// process any args that were passed

if(typeof h !== 'undefined'){

this.hours(h);

}

if(typeof m !== 'undefined'){

this.minutes(m);

}

if(typeof s !== 'undefined'){

this.seconds(s);

}

};

// the accessor methods

pbs.Time.prototype.hours = function(h){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._hours;

}

if(!isValidInteger(h, 0, 23)){

throw new TypeError('the hours value must be an integer between 0 and 23 inclusive');

}

this._hours = h;

return this;

};

pbs.Time.prototype.minutes = function(m){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._minutes;

}

if(!isValidInteger(m, 0, 59)){

throw new TypeError('the minutes value must be an integer between 0 and 59 inclusive');

}

this._minutes = m;

return this;

};

pbs.Time.prototype.seconds = function(s){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._seconds;

}

if(!isValidInteger(s, 0, 59)){

throw new TypeError('the seconds value must be an integer between 0 and 59 inclusive');

}

this._seconds = s;

return this;

};

// add functions

pbs.Time.prototype.time12 = function(){

var ans = '';

if(this._hours === 0){

ans += '12';

}else if(this._hours <= 12){

ans += this._hours;

}else{

ans += (this._hours - 12);

}

ans += ':' + intToPaddedString(this._minutes, 2) + ':' + intToPaddedString(this._seconds, 2);

ans += this._hours < 12 ? 'AM' : 'PM';

return ans;

};

pbs.Time.prototype.time24 = function(){

return '' + intToPaddedString(this._hours, 2) + ':' + intToPaddedString(this._minutes, 2) + ':' + intToPaddedString(this._seconds, 2);

};

// define a toString function

pbs.Time.prototype.toString = pbs.Time.prototype.time24;

//

// === Define Date protoype (Part 2) ===

//

// the constructor

pbs.Date = function(d, m, y){

// init data with default values

this._day = 1;

this._month = 1;

this._year = 1970;

// deal with any passed args

if(typeof d !== 'undefined'){

this.day(d);

}

if(typeof m !== 'undefined'){

this.month(m);

}

if(typeof y !== 'undefined'){

this.year(y);

}

};

// the accessor methods

pbs.Date.prototype.day = function(d){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._day;

}

if(!isValidInteger(d, 1, 31)){

throw new TypeError('the day must be an integer between 1 and 31 inclusive');

}

d = parseInt(d); // force to number if string of digits

if(!isValidateDMYCombo(d, this._month, this._year)){

throw new Error('invalid day, month, year combination');

}

this._day = d;

return this;

};

pbs.Date.prototype.month = function(m){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._month;

}

if(!isValidInteger(m, 1, 12)){

throw new TypeError('the month must be an integer between 1 and 12 inclusive');

}

m = parseInt(m); // force to number if string of digits

if(!isValidateDMYCombo(this._day, m, this._year)){

throw new Error('invalid day, month, year combination');

}

this._month = m;

return this;

};

pbs.Date.prototype.year = function(y){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._year;

}

if(!isValidInteger(y)){ // no bounds check on the year

throw new TypeError('the year must be an integer');

}

y = parseInt(y); // force to number if string of digits

if(!isValidateDMYCombo(this._day, this._month, y)){

throw new Error('invalid day, month, year combination');

}

this._year = y;

return this;

};

// define needed functions

pbs.Date.prototype.international = function(y, m, d){

if(arguments.length === 0){

// we are in 'get' mode

return intToPaddedString(this._year, 4) + '-' + intToPaddedString(this._month, 2) + '-' + intToPaddedString(this._day, 2);

}

// if we got here we are in 'set' mode

// validate the three pieces of data

if(!(isValidInteger(d, 1, 31) && isValidInteger(m, 1, 12) && isValidInteger(y))){

throw new TypeError('invalid date information - must be three integers');

}

// force the three pieces of data to be numbers and not strings

d = parseInt(d);

m = parseInt(m);

y = parseInt(y);

// test the combination is valid

if(!isValidateDMYCombo(d, m, y)){

throw new Error('invalid day, month, year combination');

}

// set the three pieces of data

this._day = d;

this._month = m;

this._year = y;

// return a refernce to self

return this;

};

pbs.Date.prototype.american = function(m, d, y){

if(arguments.length === 0){

// we are in 'get' mode

var ans = '';

ans += this._month + '/' + this._day + '/';

if(this._year <= 0){

ans += (Math.abs(this._year - 1)) + 'BC';

}else{

ans += this._year;

}

return ans;

}

// if we got here we are in 'set' mode

return this.international(y, m, d); // avoid needless duplication

};

pbs.Date.prototype.european = function(d, m, y){

if(arguments.length === 0){

// we are in 'get' mode

var ans = '';

ans += intToPaddedString(this._day, 2) + '-' + intToPaddedString(this._month, 2) + '-';

if(this._year <= 0){

ans += Math.abs(this._year - 1) + 'BCE';

}else{

ans += this._year;

}

return ans;

}

// if we got here we are in 'set' mode

return this.international(y, m, d); // avoid needless duplication

};

pbs.Date.prototype.english = function(){

var ans = '';

ans += this._day + toOrdinalString(this._day) + ' of ' + monthNameLookup[this._month] + ' ';

if(this._year <= 0){

ans += Math.abs(this._year - 1) + 'BCE';

}else{

ans += this._year;

}

return ans;

};

// provide a toString

pbs.Date.prototype.toString = pbs.Date.prototype.international;

//

// === Define DateTime protoype (Part 3) ===

//

// the constructor

pbs.DateTime = function(d, t){

// init data with defaults

this._date = new pbs.Date();

this._time = new pbs.Time();

// deal with any args that were passed

if(typeof d !== 'undefined'){

this.date(d);

}

if(typeof t !== 'undefined'){

this.time(t);

}

};

// accessor methods

pbs.DateTime.prototype.date = function(d){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._date;

}

if(!(d instanceof pbs.Date)){

throw new TypeError('require an instance of the pbs.Date prototype');

}

this._date = d;

return this;

};

pbs.DateTime.prototype.time = function(t){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._time;

}

if(!(t instanceof pbs.Time)){

throw new TypeError('require an instance of the pbs.Time prototype');

}

this._time = t;

return this;

};

// define functions

pbs.DateTime.prototype.american12Hour = function(){

return this._date.american() + ' ' + this._time.time12();

};

pbs.DateTime.prototype.american24Hour = function(){

return this._date.american() + ' ' + this._time.time24();

};

pbs.DateTime.prototype.european12Hour = function(){

return this._date.european() + ' ' + this._time.time12();

};

pbs.DateTime.prototype.european24Hour = function(){

return this._date.european() + ' ' + this._time.time24();

};

// provide a toString

pbs.DateTime.prototype.toString = function(){

return this._date.toString() + ' ' + this._time.toString();

};

})(pbs);

//

// === Test Code ===

//

// instalment 27 part 1 tests

var lunchTime = new pbs.Time();

lunchTime.hours(13);

console.log(lunchTime.toString());

var dinnerTime = new pbs.Time(17, 30);

console.log("I have my lunch at " + lunchTime.time24() + " each day");

console.log("I have my dinner at " + dinnerTime.time12() + " each evening");

// instalment 27 part 2 tests

var nextAprilFools = new pbs.Date();

nextAprilFools.day(1).month(4).year(2017);

console.log("In America the next April Fools Day is " + nextAprilFools.american());

console.log("In Europe the next April Fools Day is " + nextAprilFools.european());

// instalment 27 part 3 tests

var gonnaPrankBart = new pbs.DateTime(new pbs.Date(1, 4, 2017), new pbs.Time(15));

console.log('Gonna prank Bart good on ' + gonnaPrankBart.european24Hour() + ' his time');

// instalment 28 part 2 tests

var testDate = new pbs.Date(1, 1, 1970);

testDate.european(29, 2, 2016);

console.log('successfully converted 1 Jan 1970 to ' + testDate.toString());

// instalment 28 part 3 tests

var nextXMas = new pbs.Date();

nextXMas.international(2017, 12, 25);

console.log("I'm looking forward to getting presents on the " + nextXMas.english());

I’d like to start by drawing your attention to my implementations of the pbs.Date.prototype.american() and pbs.Date.prototype.european() functions. To avoid code duplication, both call pbs.Date.prototype.international() when invoked in setter mode (i.e. with arguments).

You can also see that all the setters in the pbs.Date prototype now call the helper function isValidateDMYCombo() to ensure it’s not possible to set an invalid date like the 31st of April 2016. Creating the helper function has allowed us to avoid massive code duplication.

At this stage our prototypes are coming on nicely, but they still have some shortcomings.

The biggest remaining problem is a subtle but very important one, and it only affects the pbs.DateTime prototype. What makes this prototype different? Instances of pbs.Date and pbs.Time contain only basic data (numbers), but, instances of pbs.DateTime contain objects – each instance of pbs.DateTime contains an instance of both pbs.Date, and pbs.Time.

A point I stressed early in the series is that variables can store numbers, strings, booleans, or references to objects. When a variable contains a value like the number 4, the string 'boogers', or the boolean true, it actually contains that value. An object can’t be stored directly in a variable. What the variable actually contains is a reference to the object, not the object itself. The object itself resides somewhere in memory, and could potentially contain a lot of data. What the variable stores is in effect the memory address of the object’s entry point. Think of it like a street address.

This subtle difference between basic values and objects becomes very important when you assign one variable equal to the value stored in another.

When you have a variable that holds a basic value, like a number, and assign another variable equal to it, the number gets copied. Each variable has its own copy of the number. Changing the number stored in one of the variables has no effect on the value stored in the other. We can prove this to ourselves with this simple code snippet:

var x = 4;

console.log('initial value of x: ' + x);

var y = x;

console.log('value of y when set equal to x: ' + y);

y += 10

console.log('after adding 10 to y we have: x=' + x + ' & y=' + y);

When you run the above, you get the following, totally unsurprising, output:

initial value of x: 4

value of y when set equal to x: 4

after adding 10 to y we have: x=4 & y=14

Variables that ‘contain’ objects do not behave like this. Why? Because they contain references to the objects, not the objects themselves.

When you have a variable that ‘contains’ an object and then create another variable and assign it equal to the first, what gets copied is the reference, not the object. You now have two copies of the same ‘address’. You have in effect created an alias to the object. The object effectively has two names, but there is still only one object. If you alter the object via one of its names, the value ‘contained’ in the other will also change. This kind of spooky action at a distance can really catch you out if you’re not careful!

Forgetting that variables can only hold references to objects results in some of the most brain-bending bugs imaginable. You could easily loose your sanity as changing one variable inexplicably (to you) breaks something hundreds of lines removed in your code. Finding these kinds of bugs can be really tricky; so you really want to avoid them. That’s why I’ve been repeating the fact that objects contain references to variables so often in this segment – don’t think it’s possible to overemphasise the point!

The code snippet below illustrates this spooky action at a distance for you:

var x = new pbs.Time(17, 30);

console.log('x represents the time ' + x.time12());

var y = x;

console.log('y represents the time ' + y.time12());

y.hours(9).minutes(0);

console.log('after altering y to ' + y.time12() + ' x is now also ' + x.time12());

Running the above produces the following output:

x represents the time 5:30:00PM

y represents the time 5:30:00PM

after altering y to 9:00:00AM x is now also 9:00:00AM

If you remember that variables contain references to objects, then this output makes perfect sense: y was set equal to the same reference as x, so of course they are the same object. If you forget that variables contains references to objects rather than the objects themselves, this behaviour will catch you by surprise every time.

At the moment, the accessor methods in pbs.DateTime are returning references to the objects contained within the instances, not references to copies of those objects. This will lead to unwanted and unexpected behaviour in one of two ways:

var t = new pbs.Time(5, 0);

var d = new pbs.Date(1, 5, 2015);

var dt = new pbs.DateTime(d, t);

console.log('dt represents: ' + dt.toString());

t.hours(10);

console.log('after editing t, dt now represents ' + dt.toString());

Running this code produces the following output:

dt represents: 2015-05-01 05:00:00

after editing t, dt now represents 2015-05-01 10:00:00

Because the constructor saved a reference to t into the new object dt instead of a copy of t, altering t produces spooky action at a distance.

We also get similar spooky action at a distance when we use the accessor methods to get one of the internal values:

var dt = new pbs.DateTime(new pbs.Date(25, 12, 2016), new pbs.Time());

console.log('dt originally represents ' + dt.toString());

var d = dt.date();

d.year(2017);

console.log('dt now represents ' + dt.toString());

This produces the following output:

dt originally represents 2016-12-25 00:00:00

dt now represents 2017-12-25 00:00:00

We never explicitly altered dt, but dt changed.

What’s the solution? Cloning!

Constructors and accessor methods that make use of objects need to store or return references to copies, or clones, of these objects, not merely copies of the original references. To make this possible, every prototype you write should contain a function named .clone(), which should return a new object that represents the same values as stored within the instance being cloned.

A clone function is basically a deep copy – if a piece of data is a value like a number, string, or boolean, just copy it. If it’s an object, clone it.

Let’s start with the simple case, and create a clone function for our pbs.Time prototype:

// define a clone function

pbs.Time.prototype.clone = function(){

return new pbs.Time(this._hours, this._minutes, this._seconds);

};

As you can see, for simple objects, clone functions are very simple things. You just need to ensure that what’s returned is a reference to a brand new object that represents the same data as the object the .clone() function was called on. We can do that by simply calling the constructor with the current internal values as arguments. (Yet another example of avoiding code duplication.)

We can see this simple clone function in action like so:

var t1 = new pbs.Time(5, 30);

var t2 = t1.clone();

console.log('t1=' + t1.toString() + ' & t2=' + t2);

t1.hours(9);

t2.hours(4);

console.log('t1=' + t1.toString() + ' & t2=' + t2);

This produces the following output:

t1=05:00:00 & t2=05:00:00

t1=09:00:00 & t2=04:00:00

As you can see, the clone starts off as an identical copy of the original. Then either can be altered without affecting the other.

Adding a clone function to pbs.Date will be very similar.

Because pbs.DateTime objects contain objects, that prototype’s .clone() function is a little more complex. Before we can create its .clone() function, we need to update the accessor methods so they clone the pbs.Date and pbs.Time objects when getting and setting. Because we wrote our constructor to use the accessor methods, we don’t need to make any changes there.

As an example, here is how we would update the .date() accessor:

pbs.DateTime.prototype.date = function(d){

if(arguments.length === 0){

return this._date.clone();

}

if(!(d instanceof pbs.Date)){

throw new TypeError('require an instance of the pbs.Date prototype');

}

this._date = d.clone();

return this;

};

The changes are very subtle – all we had to do was change return this._date; to return this._date.clone();, and this._date = d; to this._date = d.clone();. Similar changes need to be made to the other accessor (.time()).

Once that’s done, we can add a .clone() function just like we did for pbs.Date and pbs.Time.

Challenge

Add .clone() functions to your pbs.Date and pbs.Time prototypes. Next, update the accessors in your pbs.DateTime prototype to clone the values they get and set. Then, add a .clone() function to the pbs.DateTime prototype.

You’ll know your changes have worked when the following code behaves as expected, without any spooky action at a distance:

var d = new pbs.Date(17, 3, 2017);

var t = new pbs.Time(11, 0);

var dt = new pbs.DateTime(d, t);

console.log('d=' + d + ', t=' + t + ' & dt=' + dt);

d.year(2018);

t.minutes(15);

console.log('d=' + d + ', t=' + t + ' & dt=' + dt);

var t2 = dt.time();

t2.seconds(15);

console.log('t=' + t + ', t2=' + t2 + ' & dt=' + dt);

HTML Glyph Icons

In the previous instalment, we saw how we could use images to enhance the clarity of our buttons. The concept of adding an icon to help the user is sound, but using pixel-based images is not. The icons need to be scalable. So we need some kind of vector-based solution.

Because this is a very common problem, an interesting solution has been devised that combines a collection of technologies to produce a solution that’s powerful, and yet simple to use. The solution combines scalable vector graphics, web fonts, and CSS. The resulting icons are often generally referred to as glyphs, or glyph icons, and collections of these icons as glyph icon sets, or iconic fonts.

While pre-made glyph icon sets are very easy to use, creating your own is quite laborious. Thankfully, you don’t have to! You can buy commercial glyph icon sets like Glyphicons, or you can use free open source glyph icon sets like the one provided by Font Awesome. That’s what we’ll be using in this series.

Using Font Awesome

If you plan on using Font Awesome for real world projects, you should create a free account on their CDN (content delivery network), and generate a project-specific download URL as described on their get started page.

For this series though, we’ll be using a download URL created with my account.

When you create your own download URL, you can choose which version of the icon set your link will lead to. You can choose to use either a JavaScript-based variant of the icon set which includes some extra automation, or a plain CSS variant. For simplicity, the link I generated for this series is to the plain CSS variant.

So, for our purposes, including Font Awesome into a web page is as simple as adding the following line inside the head section:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://use.fontawesome.com/9437c02941.css" />

Once you’ve done this, you can turn any empty inline tag into an icon by adding two CSS classes to it: fa, and then the class for the icon you want. You can find all the icons, and their classes, using the icon search page on the Font Awesome website.

What tag you should use for these icons is a bit of a thorny issue. The Font Awesome website suggests using the <i> tag. Why? Because it takes up the least possible amount of space in your HTML source.

I would strongly advise against that approach – it’s semantic nonsense! The correct tag, semantically, is the <span>, so that’s what I’m going to use in all my examples.

So – as a quick example, assuming you have included Font Awesome into your page, you can add a thumbs-up icon anywhere in your page like so:

<span class="fa fa-thumbs-up"></span>

The sizing of the icon is determined by the font size. If you include an icon in a header, you’ll see it larger than when you include it in a paragraph.

Because these icons are actually characters in a font, their colour is determined by the text colour set for the part of the page where they appear.

So, to get icons rendered in the default way with the same size and colour as your text, you just create an empty <span> and give it the class fa and the class for the icon you would like. However, you can do more! Font Awesome also defines a number of modifier classes which you can add as extra classes along with the two you always need.

You can make icons a little bigger than the text by adding the class fa-lg (for large), or you can make the icons bigger still with fa-2x, fa-3x, and so on up to fa-5x, which makes simply massive icons.

You can also control the rotation of your icons with the special classes fa-rotate-90, fa-rotate-180, and fa-rotate-270. You can mirror them with fa-flip-horizontal and fa-flip-vertical.

Another thing you can do is add a subtle border around your icon by adding the class fa-border.

You can also make your ions effectively float left or right by adding the fa-pull-left or fa-pull-right classes. This is particularly useful when combined with large icon sizes and perhaps also borders.

There are also classes provided to make it easy to use these icons in bulleted lists. To do this, simply add the class fa-ul to the <ul> tag for the list, and add your icon as the first item within the <li> tag, and, with the additional class fa-li, e.g.:

<h2>Underpants Gnomes Check-list:</h2>

<ul class="fa-ul">

<li><span class="fa-li fa fa-check-square-o"></span> Steal underpants</li>

<li><span class="fa-li fa fa-square-o"></span> ???</li>

<li><span class="fa-li fa fa-square-o"></span> Profit</li>

</ul>

Finally, you can stack two icons on top of each other to make compound icons. First, you create a <span> that will contain the two icons and give it the class fa-stack. If you want to make your whole stack bigger than normal, you can add fa-lg etc. to this outer span.

Then, you add the two icons inside this outer <span>. The first one will be below the second one. To make the icons stack properly, you’ll need to make one bigger than the other. You specify which you want as which by adding the class fa-stack-1x to the one you’d like to be the smaller of the two, and fa-stack-2x to the other. If you use a background icon that’s a solid shape, you might need to invert the foreground icon by adding the class fa-inverse to it.

As an example, you could stack an inverse Apple logo over a heart as follows:

<span class="fa-stack">

<span class="fa fa-heart fa-stack-2x"></span>

<span class="fa fa-apple fa-stack-1x fa-inverse"></span>

</span>

You can also stack the larger logo over the smaller one, and you can add colours to one or the other. You could synthesise a large no photography sign like so:

<span class="fa-stack fa-5x">

<span class="fa fa-camera fa-stack-1x"></span>

<span class="fa fa-ban fa-stack-2x" style="color: red"></span>

</span>

Finally, bringing all this back to HTML forms, we can redo our buttons from last time, but with nice icons instead of images:

<p>The buttons below include glyph icons to make it clearer what they do:</p>

<form action="javascript:void(0);">

<p style="text-align: center">

<button type="reset" class="pbs">

<span class="fa fa-refresh"></span>

Reset

</button>

<button type="button" class="pbs">

<span class="fa fa-remove"></span>

Cancel

</button>

<button type="submit" class="pbs">

<span class="fa fa-save"></span>

Save

</button>

</p>

</form>

Below is the file pbs29.html from the zip file for this instalment. It shows examples of all the uses of Font Awesome described above:

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>PBS 29 - Font Awesome Demo</title>

<!-- Include Font Awesome using the PBS CDN link -->

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://use.fontawesome.com/9437c02941.css" />

<!-- Include the same CSS for buttons as used in PBS 28 -->

<style type="text/css">

/* dim the text on reset buttons */

button.pbs[type="reset"]{

color: dimgrey;

}

/* make the text on ordinary buttons blue */

button.pbs[type="button"]{

color: DarkBlue;

}

/* bold the text on submit buttons and make it dark green */

button.pbs[type="submit"]{

font-weight: bold;

color: DarkGreen;

}

/* style images within buttons */

button.pbs img{

height: 0.9em;

vertical-align: baseline;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>PBS 29 - Font Awesome Demo <span class="fa fa-thumbs-up"></span></h1>

<p>Notice the big thungs up in the header above. Using the same code in a paragraph produces a small thumbs up <span class="fa fa-thumbs-up"></span>!</p>

<p>Because these icons are just characters in a font, you can have them in any colour:

<span class="fa fa-battery-full" style="color: green"></span>

<span class="fa fa-battery-half" style="color: orange"></span>

<span class="fa fa-battery-empty" style="color: red"></span>

</p>

<p>While the size is determiend by the font, you can intentionally make them bigger than they would normally be <span class="fa fa-bullhorn fa-lg"></span>, or even MUCH bigger <span class="fa fa-bullhorn fa-5x"></span>.</p>

<p>You can also rotate your icons:

<span style="color: orange">

<span class="fa fa-bolt"></span>

<span class="fa fa-bolt fa-rotate-90"></span>

<span class="fa fa-bolt fa-rotate-180"></span>

<span class="fa fa-bolt fa-rotate-270"></span>

</span>

</p>

<p>You can also flip/mirror your icons both horizontally and vertically:

<span class="fa fa-volume-control-phone"></span>

<span class="fa fa-volume-control-phone fa-flip-horizontal"></span>

<span class="fa fa-volume-control-phone fa-flip-vertical"></span>

</p>

<p>You can also add subtle boarders to your icons so this <span class="fa fa-lock"></span> becomes this <span class="fa fa-lock fa-border"></span>.</p>

<p>Icons can also be floated to do fun things like this:</p>

<blockquote><span class="fa fa-quote-left fa-2x fa-border fa-pull-left"></span>

<p>I wandered lonely as a cloud<br />

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,<br />

When all at once I saw a crowd,<br />

A host of golden daffodils;<br />

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,<br />

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.</p>

<p>Continuous as the stars that shine<br />

and twinkle on the Milky Way,<br />

They stretched in never-ending line<br />

along the margin of a bay:<br />

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,<br />

tossing their heads in sprightly dance.<br />

The waves beside them danced; but they<br />

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:<br />

A poet could not but be gay,<br />

in such a jocund company:<br />

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought<br />

what wealth the show to me had brought:</p>

<p>For oft, when on my couch I lie<br />

In vacant or in pensive mood,<br />

They flash upon that inward eye<br />

Which is the bliss of solitude;<br />

And then my heart with pleasure fills,<br />

And dances with the daffodils.</p>

<p>- by William Wordsworth</p>

</blockquote>

<p>Icons can also be stacked. This is an inverted Apple logo stacked on a heart

<span class="fa-stack">

<span class="fa fa-heart fa-stack-2x"></span>

<span class="fa fa-apple fa-stack-1x fa-inverse"></span>

</span>, and this is a large no photography sign created by putting a red ban symbol over a camera icon:<br />

<span class="fa-stack fa-5x">

<span class="fa fa-camera fa-stack-1x"></span>

<span class="fa fa-ban fa-stack-2x" style="color: red"></span>

</span>

</p>

<p>There are also pre-made classes designed to allow you to use icons in lists:</p>

<ul class="fa-ul">

<li><span class="fa-li fa fa-check-square-o"></span> Steal underpants</li>

<li><span class="fa-li fa fa-square-o"></span> ???</li>

<li><span class="fa-li fa fa-square-o"></span> Profit</li>

</ul>

<h2>Buttons With Icons</h2>

<p>The buttons below include glyph icons to make it clearer what they do:</p>

<form action="javascript:void(0);">

<p style="text-align: center">

<button type="reset" class="pbs">

<span class="fa fa-refresh"></span>

Reset

</button>

<button type="button" class="pbs">

<span class="fa fa-remove"></span>

Cancel

</button>

<button type="submit" class="pbs">

<span class="fa fa-save"></span>

Save

</button>

</p>

</form>

</body>

</html>

You can view your local copy of this file in your browser, or view a version on my web server here.

Final Thoughts

We’ll start the next instalment with more JavaScript prototype revision. First, we’ll take a look at my sample solution to the challenge set in this instalment. Then we’ll move on to add another important additional feature to all three of our prototypes – the ability to do comparisons.

We’ll then move on to learn about a W3C standard that is very important for HTML forms, especially forms that make use of glyph icons – ARIA (Accessible Rich Internet Applications).