PBS Tidbit 11 of Y: A PowerShell Teaser

Somewhat ironically, since finishing our long series on Bash scripting I’ve been almost exclusively writing scripts in a completely different language, PowerShell! Being a Microsoft language you’d be forgiven for assuming that means I’ve moved to Windows and started trying to automate things there, but you’d be mistaken, I’m still very much a Mac user! So what gives? Despite what its origins may suggest, the core PowerShell environment is both open source and cross-platform, running just fine on Mac and Linux as well as Windows.

Think of this Tidbit as being like a movie trailer — it’s intended to pique your interest, and to give you a broad sense of why you might want to spend some time making friends with PowerShell, but it’s by no means a detailed tutorial. This instalment is also intended as a kind of community survey. If there’s sufficient community interest, we could spend the second part of 2025 learning PowerShell like we learned Bash. I don’t only want to hear from people who would like us to do that, though; I’d also like to hear from those in the community who think it’d be a waste of time and effort. Have your say on the PBS channel in the Podfeet Slack!

Matching Podcast Episodes

PBS Tidbit 11A dated 2025-01-02:

You can also Download the MP3

Read an unedited, auto-generated transcript with chapter marks: PBS_2025_01_02

PBS Tidbit 11B dated 2025-01-18

You can also Download the MP3

Read an unedited, auto-generated transcript with chapter marks: PBS_2025_01_18

What Drew me to PowerShell?

Like with most things Microsoft, my first introduction to PowerShell was involuntary, and I dipped my toe in reluctantly! But within just a few hours I started to get the sense that there was a lot of “there” there. This wasn’t some kind of half-baked slap-dash replacement for DOS batch files but a full-featured and very modern re-imagining of what a shell could be. Microsoft started with a completely blank slate. They took everything we all learned from the decades of advances in programming languages and concepts since C and the original Unix shell were created in the 70s and built a thoroughly modern cross platform, open source command line, and scripting environment.

The way I see it, “Imagine what the Unix guys would have done if they knew then what we know now” really is good way to describe PowerShell. PowerShell takes the sh/Bash/zsh idea of creating lots of simple single-purpose commands and chaining them together to do powerful things, and combines it with a Java-like cross-platform runtime environment. Deep under the hood it’s actually the new(ish) open source .NET Core runtime environment (the replacement of the old proprietary .NET Framework), but that’s only important when you want to leverage the power that brings in your scripts. The rest of the time .NET generally stays out of sight and out of mind!

PowerShell Versions & Tooling

Like Apple’s young language Swift, PowerShell has evolved a lot from its initial release to the current production release. For a good experience, be sure you’re using the latest version, or at least the most recent Long Term Support (LTS) version. As of Jaunary 2025 that’s version 7.4.* or 7.2.*.

There’s a section in the docs describing all the different ways to install PowerShell on all the different platforms, but on the Mac by far the simplest method is to use HomeBrew:

brew install powershell/tap/powershell

Once you have PowerShell installed you can start a shell with the command pwsh.

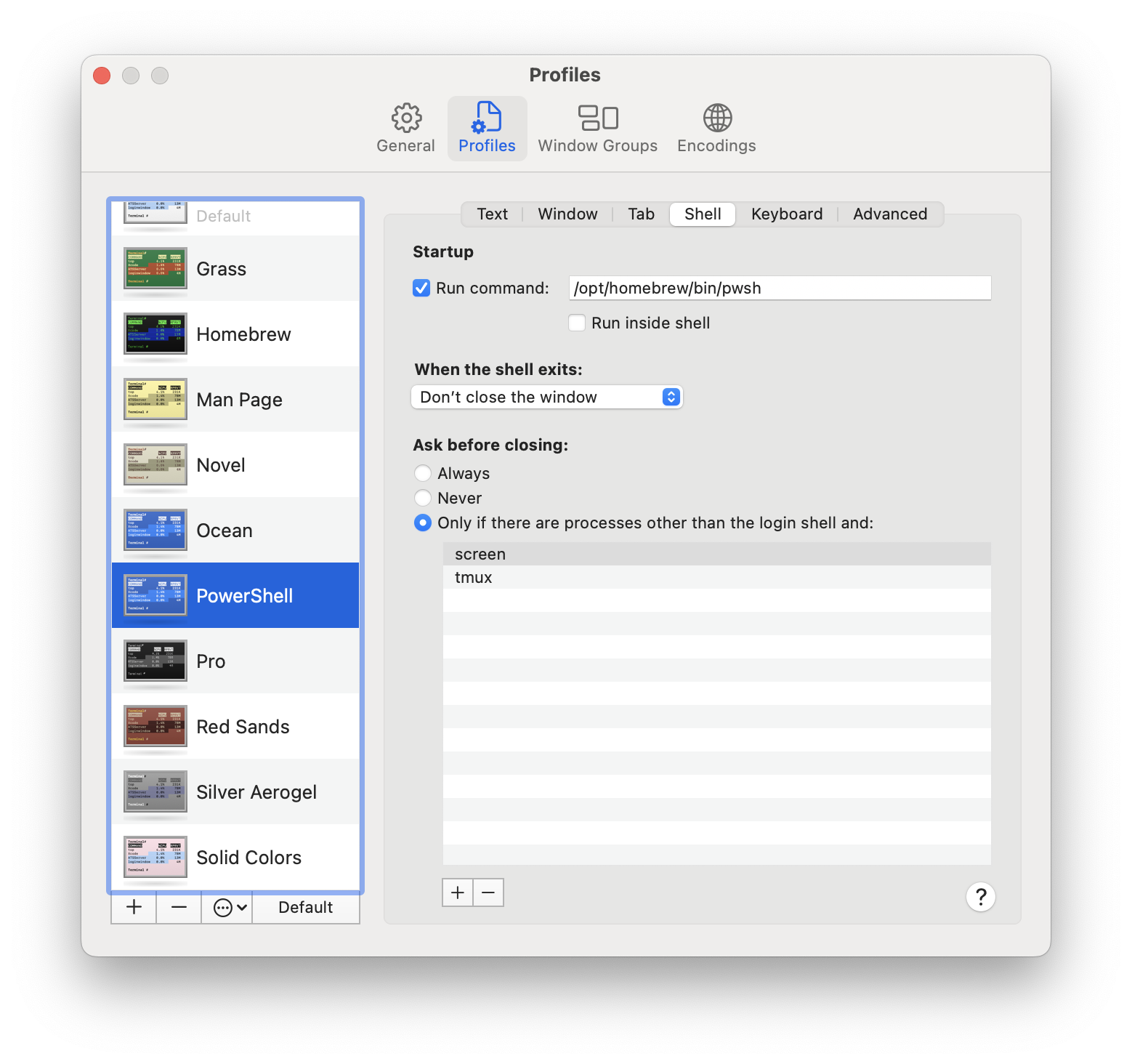

If you’re going to use the Terminal app for running PowerShell commands you can create a new profile for quick access. The important settings are under the Shell tab in the profile settings, specifically, the Run command needs to be set to the full path to pwsh (which you can get by running which pwsh) and to un-tick the Run inside shell checkbox. On windows, PowerShell terminals were blue for many years to distinguish them from command prompts, so I like to create my Mac PowerShell Terminal profile by cloning the built-in Ocean profile and then editing the two settings mentioned above on the Shell tab of my clone. These are the settings I use:

On Windows I’d recommend installing Microsoft’s modern Windows Terminal app for a nicer CLI than the default one that ships with the Windows version of PowerShell 7.

When you’re ready to start writing PowerShell scripts, I’d strongly recommend switching from a Terminal to an IDE. Specifically, I recommend using the open source cross platform VS Code with Microsoft’s official PowerShell plugin. This plugin kicks into gear when you open a PowerShell script file (a .ps1 file), at which point it will open a Terminal within VS Code which you can use to test your script in the same UI you’re using to write it. The plugin will also give you useful tool-tips and completion suggestions. It’s possible you’ll need to re-start VS Code for the plugin to be fully set up and working (Allison ran into some issues I don’t remember having).

Speaking of IDEs, I strongly suggest recommend adding a Requires comment to the very top of all your scripts to explicitly mark the version of PowerShell you used to develop and test the script. That will help both PowerShell itself and your IDE and/or AI helper handle things properly in future as PowerShell continues to evolve over time. As of January 2025 I’m adding the following as the very first line in all my scripts:

#Requires -Version 7.4

The Big-Picture — PowerShell’s Philosophy

PowerShell’s philosophy is different to that of both Bash and JavaScript, and the route to a positive experience is to lean into that fact. To have a good JavaScript experience you need to think about the world in a JavaScripty way, to have a good experience in Bash you need to think about the world in a Bashy way, and to have a good PowerShell experience you need to think about the world in a PowerShelly way.

As I type these notes I can already hear Allison getting impatient and wanting to see some commands, so to get that out of the way, let’s do the traditional Hello-World in PowerShell

Open a PowerShell prompt by either:

- Opening a regular terminal and entering the command

pwsh - Using a custom Terminal profile that always runs the PowerShell shell

- Using the PowerShell terminal provided by your IDE

- Or, if you’re on Windows, using the dedicated PowerShell 7 app of a PowerShell tab in the Windows Terminal app

On your PowerShell prompt, enter the following command:

Write-Host 'Hello World!'

With that done I now beg your forbearance while we spend some time exploring PowerShell’s philosophy before we end with a very quick syntax overview 🙂

The Structure of Commands

This is an area where PowerShell has the same view of things as Bash, DOS, etc. Commands are lines of text with the ‘parts’ being delimited by spaces. The first ‘part’ has to be a command of some kind or an operator. If the first part is an operator things can get a little more complicated, just like in Bash, but most of the time the first part is a command of some kind, and all the other parts become the arguments.

This is the perfect opportunity to flag an important point of jargon. For all intents and purposes argument and parameter are synonyms. So far in this series we’ve chosen to use argument because that’s the jargon used in both the JavaScript and Bash communities and documentation. However, PowerShell’s authors made the other choice, so in syntax, documentation, and the broader community, the word you’ll see is parameter. For your own sanity, and for ease of searching online, I strongly recommend that when you think about PowerShell, you think about parameters rather than arguments.

It’s Functions all the Way Down

When reading the docs I was initially very frustrated that I could find good docs on how the standard built-in commands work, and good docs on writing my own functions, but there didn’t seem to be any docs on writing scripts, and I wanted to write scripts!

The reason for my confusion is that I’d skipped over the start of the documentation where the hand-wavy stuff lives and missed a fundamental concept — in PowerShell scripts are just functions in their own file!

It actually goes deeper than that, commands are just fancy functions that are available in the shell!

If we take our Hello World command we can turn it into a very basic function by simply wrapping it in a function definition:

function Write-HelloWorld {

Write-Host 'Hello World!'

}

Note: when pasting multi-line PowerShell snippets like function declarations, paste them in all at once as once paste!

If you paste this into a PowerShell terminal you can then use your function exactly like it was any other PowerShell command:

Write-HelloWorld

We can now convert our function to a script we can run at any time by moving just the function’s contents into a file with a .ps1 extension. Let’s create Write-HelloWorld.ps1 and give it just the following contents:

#Requires -Version 7.4

Write-Host 'Hello World!'

Note: it is possible to configure PowerShell to search for scripts in various special locations, but that’s outside the scope of this teaser, so any example files you choose to create when following along will only be executable if the file and your PowerShell terminal are in the same folder!

We can now run our script using PowerShell’s version of the Bash dot command which is & followed by a file path:

& ./Write-HelloWorld.ps1

Reinvented ‘Plumbing’ — Data and Messages are Separated

PowerShell shares the Unix philosophy of building complex solutions by chaining together simple commands. It even shares the same operator for connecting the output from one command to the input of another — the perfectly named pipe (|)!

But this is where the similarities end. In Bash, the output that would normally go to the human is the output the pipe diverts to become the input to the next command, so there is no difference between messages to the user and output data — it all goes into the same stream. As a result, when you redirect that one stream, you redirect both. This means Unix/Linux terminal commands designed to output data only output data. They don’t give the user any messages, because if they did, it would mess up the next command in the pipeline. PowerShell separates these two roles, dedicating the pipeline to just data and providing four separate message output streams.

A Data-Only Pipeline

Any PowerShell function can optionally accept data inputs from the pipeline, hence any script can optionally accept data inputs from the pipeline, and so can any command (since it’s functions all the way down).

Because the pipeline is purely for data, it’s not limited to streams of characters, the data can be of any type, so deep down it is in fact all objects. Not only can the data be of any type, it can be chunked into separate pieces, so it’s not one flow of characters, but a sequence of individual items which each get processed one-by-one. While the Unix pipeline carries a constant flow of characters, making it very river-like, the PowerShell pipeline is much more like a conveyor belt with individual pieces of data.

If a command supports the pipeline, then you can send arbitrarily many pieces of data to it!

To use the pipeline in your own functions you need to do the following:

- If you want to accept data from the pipeline you need to define a named parameter for receiving the pieces of data

- To process data from the pipeline, you need to use the optional

begin,process, andendsyntax for your function definition - You need to use the

Write-Outputcommand to send data to the pipeline.

As an illustration, let’s define a function that doubles a number, first as a regular function, and then as a function that accepts numbers from the pipeline.

Here’s our basic function:

function Get-DoubleValue {

param(

[double]$Number

)

return $Number * 2

}

After pasting that function into our shell we can call it with:

Get-DoubleValue -Number 5

Which will output 10.

We can convert this to a pipeline function by mapping the $Number parameter to the pipeline, issuing a process block, and outputting the result to the pipeline:

function Get-DoubleValue {

param(

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeline=$true)]

[double]$Number

)

process {

Write-Output ($Number * 2)

}

}

We can completely ignore the function’s new super-power and continue to use it as before:

Get-DoubleValue -Number 5

But we can now pipe numbers to the command:

5 | Get-DoubleValue

In fact, we can pipe as many numbers as we’d like!

1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | Get-DoubleValue

You can see that what PowerShell does is repeat the process {} block once for each input in the pipeline, so pipeline functions are actually loops with some superpowers!

Speaking of those superpowers, while many functions that support the pipeline will act symmetrically, producing one output for each input, that’s not a requirement. As well as a process {} block, you can also use begin {} and end {} blocks to do more powerful things. As their names imply the begin {} block will get executed once before the first pipeline input is processed, and the end {} block once after the last input is processed. This allows pipeline functions to generate additional outputs, or collapse inputs to a single output.

As an example, let’s make a function that sums numbers:

function Get-Sum {

param(

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeline=$true)]

[double]$Number

)

begin {

$Total = 0

}

process {

$Total += $Number

}

end {

Write-Output $Total

}

}

We can now sum numbers with commands like:

5,7 | Get-Sum

But, we can double and then sum by pipelining our two functions:

1,2,3 | Get-DoubleValue | Get-Sum

This gives 12, which is the right answer, but it’s not showing us any more information that a typical Unix command would, so let’s look at how PowerShell does message output.

Four Message Streams

In Bash, we know that while the pipe only connects the standard output to the next command’s input, there is actually one more standard stream: the standard error stream.

PowerShell expands on this idea by adding four distinct streams for outputting messages to the user, each for a different severity level:

- Verbose output — usually only relevant when debugging, and hidden by default. In your scripts you write to this stream with the

Write-Verbosecommand. - Informational output — normal output when nothing goes wrong. In your own scripts you write this kind of output with

Write-Host. - Warnings — something’s gone wrong, but was at least partially recoverable. You can output your own warnings with

Write-Warning. - Errors — something’s failed! You can output your own errors with

Write-Error.

To see why having data and messages separate is powerful, let’s add some message output to our doubling function:

function Get-DoubleValue {

param(

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeline=$true)]

[double]$Number

)

process {

$Answer = $Number * 2

Write-Host "$Number doubled is $Answer"

Write-Output $Answer

}

}

Now, let’s re-run our pipeline to double and then sum:

1,2,3 | Get-DoubleValue | Get-Sum

Notice that we see the messages telling us what one, two, and three doubled are, but adding those messages did not mess up the summing function’s inputs, it still only saw 2, 4, & 6 as its inputs, so it still calculated 12!

What About Redirecting to Files?

So far we’ve only focused on one kind of ‘plumbing’ in Unix/Linux, piping, but what about stream redirection, i.e. the Bash redirection operators like > & >>, etc.? If you think about it, these operators are also double-jobbing. They are used for two distinct purposes:

- To send data to files

- To send outputs to logs

Again, PowerShell separates these tasks, providing separate dedicated tools for each purpose:

- Data gets written to files with an appropriate output command, e.g.

Out-File. - PowerShell provides a dedicated logging feature called Transcripts, and errors & warnings can be captured in variables.

This is the break point between podcast episode PBS Tidbit 11A & PBS Tidbit 11B.

Argument Sanity with Parameter Definitions

Again, to understand what PowerShell does differently, let’s remind ourselves of how arguments work in Bash — basically, it’s the Wild West! The arguments just arrive as strings in a pseudo array, and it’s up to the programmer to group them into some kind of logical structure. In theory, anything goes, but thankfully some conventions have emerged thanks to popular tools like getops. But the bottom line remains, the best we can hope for as users is that the developers of the command we’re thinking of using choose to be consistent, follow some kind of convention, and provided a good man page!

PowerShell could not be more different — if you want your functions, and hence your scripts or commands, to support parameters, you need to define them explicitly! We’ve already seen hints of this in our little example functions which define their parameter with the param () function.

In PowerShell parameters come in two flavours — positional, and named.

When presented with the raw list of command line parts PowerShell starts by looking for named parameters, and removing them from the list. Whatever’s left after that are the positional parameters.

Named parameters are those that start with a single -, and what comes after is their name. In other words -SomeName on the CLI becomes $SomeName in the code.

Named parameters come in two flavours; switches which, like getopts flags in bash, have no value, and regular named parameters which get their value from the next raw command line part. So a named switch -MySwitch becomes $MySwitch with a value of True, and a regular named parameter -SomeNumber 42 becomes $SomeNumber with the value 42.

This begs the question, what happens to the positional parameters? To support positional parameters you need to map them to named variables. In other words, you programatically say that the first positional parameter will be interpreted as this named parameter, the second as this one, and so on. You can also map all remaining positional parameters to a named array parameter, which could become an array of any size, including an empty array.

Defining Parameters with param ()

All of a function’s parameter definitions need to go into a single call to param () at the top of the function/script before the first line of regular code.

Each individual parameter definition can span multiple lines, but the last line of the definition needs to be the one that gives that parameter its name, and a , is used to separate the definitions. This means that the simplest parameter definition is simply:

param (

$ParameterName

)

Adding Types

However, it is very strongly encouraged to specify a type for each parameter, which you do by pre-fixing the parameter name with the type enclosed in square brackets. For example, to define four parameters with the most common types, you would use code of the form:

param (

[string]$MyStringParameter,

[int]$MyIntegerParameter,

[double]$MyDecimalNumberParameter,

[switch]$MySwitchParameter

)

Notice the commas at the end of the first three parameter definitions to separate them from the following ones. Also notice the lack of a comma on the last one, PowerShell does not tolerate trailing commas, they are considered syntax errors.

Why Add Types?

Firstly, adding the type takes very little effort, so the cost of following the developer guidelines is low. But don’t worry, there are rewards beyond just feeling like you’re doing it right 🙂

When you add a type you get two very useful PowerShell behaviours:

- Automatic type coercion — if possible, PowerShell will auto-convert the input received to the type specified. For example, if a function defines a parameter as being of type integer, and a decimal number gets passed instead, PowerShell will automatically round the number to the nearest integer.

- Automatic type validation — when coercion is not possible, PowerShell will throw an error before even wasting resources calling the function.

Adding Default Values

By default, the default value of every parameter is Null, so if a parameter is defined in the function but not passed when calling the function it will be null. We don’t have to have that default, we can assign any default value we like right within the parameter definition using the standard assignment operator, =.

As an example, let’s create a new function similar to our Write-HelloWorld function that defaults to saying hello to the world, but can say hello to anything:

function Write-Hello {

param (

[string]$Target = 'World'

)

Write-Host "Hello $Target!"

}

If we call this function with no arguments we’ll see that $Target defaults to 'World':

Write-Hello

# prints: Hello World!

But now we can also say hello to some waffles:

Write-Hello -Target 'Waffles'

# Prints: Hello Waffles!

Adding Parameter Options

As well as defining the parameter names and types, we can add parameter options to each parameter using the [Parameter()] syntax, and we can add additional data validations beyond just the base type using other syntaxes.

The Parameter() function can be used to enable many powerful behaviours, but I want to draw your attention to just three, one which we’ve already seen explicitly, one who’s effects we’ve seen implicitly, and an entirely new one:

- The

ValueFromPipelineparameter option is use to map data arriving via the pipeline to a specific named parameter. We’ve seen this syntax in our example functions in the previous section, e.g.:param( [Parameter(ValueFromPipeline=$true)] [double]$Number ) -

The

Position=parameter option is used to map a specific positional parameter to a named parameter. The value for this option should be an integer, and the first positional parameter is numbered0. We have seen this kind of positional parameter in use in our calls toWrite-Host, where we passed our string to print without naming it. Under the hoodWrite-Hostmaps the first un-named parameter to the named parameter-Message, soWrite-Host 'Hello World!'is equivalent toWrite-Host -Message 'Hello World!'. - The

Mandatory=$trueparameter option tells PowerShell that the function can’t execute without a value for this parameter.

Let’s cement all this by updating our Get-DoubleValue function yet again to map the first positional parameter to the named parameter $Number, and to make that parameter mandatory:

function Get-DoubleValue {

param(

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeline=$true, Position=0, Mandatory=$true)]

[double]$Number

)

process {

$Answer = $Number * 2

Write-Host "$Number doubled is $Answer"

Write-Output $Answer

}

}

We can now double a number without needing to explicitly name the parameter:

Get-DoubleValue 5

Why Defining Parameters Matters

Having these kinds of rigorous parameter definitions has some powerful advantages:

- PowerShell’s shell can offer help by:

- Automatically prompting for missing mandatory parameters — e.g. running our most recent

Get-DoubleValuefunction with no arguments results in a prompt for a number. - Providing tab-completion for parameters — e.g. typing

Write-Error -Mand hittingtabwill expand the parameter to-Messages. This also works for any functions/scripts you write — try typingGet-DoubleValue -Nand hittingtab!

- Automatically prompting for missing mandatory parameters — e.g. running our most recent

- IDEs can provide more informative tooltips and autocompletes for developers.

- The built-in help system can show the parameters any function/command/script can accept — e.g.

Get-Help Get-DoubleValueshows that the function we defined accepts one parameter namedNumber.

Some Refreshing Consistency with Common Parameters

Another Unix/Linux niggle PowerShell addresses is a lack of consistency in how different commands provide standard functionality like enabling debugging mode.

Remember, in Unix/Linux anything goes, so while some conventions have emerged, you just can’t make any assumptions. Even the simplest things are not really standardised. Sure, many Unix/Linux commands use -v to enable verbose mode, but many others use that same flag to output their version number!

PowerShell provides some sanctuary from this chaos through a documented list of standard parameters for all built-in commands. These standard parameters aren’t all mandatory, so some are only available on some commands, but when they’re available, they’ll always do the same thing.

While the core language religiously implements these common parameters on all commands, that’s not where the sanity ends! Since a command is just a fancy function, and since scripts are just functions in a file by themselves, the feature is actually available in commands, scripts, and functions, i.e. everywhere you use parameters. To add support for these refreshing standards to your own code you simply need to prefix your parameter definitions with a line of the form [CmdletBinding()], and you’re done!

To see how simple this is, let’s update our doubling function so it supports debugging with -Verbose:

function Get-DoubleValue {

[CmdletBinding()]

param(

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeline=$true, Position=0, Mandatory=$true)]

[double]$Number

)

process {

$Answer = $Number * 2

Write-Verbose "$Number doubled is $Answer"

Write-Output $Answer

}

}

We’ve just made two changes:

- Added the binding for the standard parameters as the first line of the function

- Replaced our call to

Write-Hostfor writting regular messages toWrite-Verbosefor writing debug messages.

If we call our function normally we now just see the answers again:

1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | Get-DoubleValue

Given how simple this function is that seems much better default behaviour than writing a message each time as well as outputting the doubled value. But we haven’t removed our messaging lines, we’ve just changed the stream they write to, so how can we see them again? Simple, by adding the standard -Verbose switch parameter:

1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | Get-DoubleValue -Verbose

Now we don’t just get our messages back, but they’re explicitly rendered as debug information!

The aforementioned documentation describes the full set of common parameters, but here are the ones I use most often:

-Verboseto enable verbose output-WhatIfto enable dry-run mode, only available on commands that perform changes or destructive actions.-ErrorActionto specify how the command should handle an error. I generally use this to force a critically important command to succeed or kill the entire script with-ErrorAction Stop.

Better man Pages with a Built-in Comment-Based Help System

We’ve already seen a little of what PowerShell’s help system can do when we were discussing parameter definitions, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg!

In the Unix/Linux world, we know that developers can choose to add documentation for their commands to a system’s manual, and those pages can be accessed from the command line via the man com

mand. When a developer writes no documentation, there is no man page at all. Because of PowerShell’s parameter definitions, every command, function, and script gets at least a skeleton help entry. We can view those with the Get-Help command.

For now, our doubling function does nothing to provide any exploit documentation, and yet, it already has a basic help page which we can view with the command Get-Help Get-DoubleValue:

NAME

Get-DoubleValue

SYNTAX

Get-DoubleValue [[-Number] <double>] [<CommonParameters>]

ALIASES

None

REMARKS

None

It’s not much, but it’s better than nothing! We can immediately see that the command defined one parameter,-Number, that it’s of type double (a decimal number), and that the command supports common parameters.

For comparison, let’s see what the help system has for a standard command like Write-Error by running:

Get-Help Write-Error

You definitely see more, but if this is the first time you’ve used the help system, you may be seeing a lot less than you could. If you’re using only the basic documentation library your output will end with a remark telling you that you can download more help by running the command Update-Help, so let’s do that and then re-run the help command for Write-Error.

You now get a lot of information! But again, notice at the bottom there’s a remark telling you there’s even more information available if you’d like to dig deeper. To see more information add the -Detailed flag, and to see even more still, add the -Full flag. That’s almost certainly more than you really want, but it’s good to know that that level of information is at your fingertips!

Most of the time the thing you need most often is just an example, so you can also filter the output down to just that section with -Examples:

Get-Help Write-Error -Examples

That’s already pretty powerful. But is there a way we can enrich the help pages for our own functions/scripts? Of course there is 🙂

Again, PowerShell is building on what has come before, and it provides a comment-based syntax similar to the third-party ESDoc tool we used for documenting our JavaScript code previously. PowerShell’s syntax is actually simpler because the formalised parameter definitions take care of a much of the work we needed to do on our ESDoc comments. For the most part, all you need to do in PowerShell is add some text and examples to augment the automatically derived information.

When you take the time to add documentation comments to your own code your IDE can leverage that to give more informative tool tips etc., and, with just one caveat, you can read your own documentation using the Get-Help command.

The one caveat is that Get-Help can only read documentation comments from files, so when you just copy-and-paste functions into the terminal Get-Help won’t see your additional information. To be able to see the documentation for your own code with Get-Help you need to do one of two things:

- Convert your functions to scripts

- Define your functions in modules

Out side of contrived examples you’re always going to be doing one of these things anyway, so this caveat is not really an issue.

As a simple example, let’s add some documentation to our doubling function by converting it to a script.

Save the following to a file named Get-DoubleValue.ps1:

#Requires 7.4

<#

.SYNOPSIS

Double numbers.

.DESCRIPTION

Double a given number by multiplying it by two.

.PARAMETER Number

The number to be doubled.

.INPUTS

System.Double. Values for the Number parameter.

.OUTPUTS

System.Double. The doubled number.

.EXAMPLE

PS> & ./Get-DoubleValue.ps1 -Number 5

10

.EXAMPLE

PS> 5,10,20 | & ./Get-DoubleValue.ps1

10

20

40

#>

[CmdletBinding()]

param(

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeline=$true, Position=0, Mandatory=$true)]

[double]$Number

)

process {

$Answer = $Number * 2

Write-Verbose "$Number doubled is $Answer"

Write-Output $Answer

}

We can now run our script using the & operator, e.g.:

& ./Get-DoubleValue.ps1 5

And:

1,2,3,4,5 | & ./Get-DoubleValue.ps1

But what’s more, we can now see the documentation we added in the speically formatted comments with the Get-Help command:

Get-Help ./Get-DoubleValue.ps1

This produces the following output:

NAME

/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/Get-DoubleValue.ps1

SYNOPSIS

Double numbers.

SYNTAX

/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/Get-DoubleValue.ps1 [[-Number] <Double>]

[<CommonParameters>]

DESCRIPTION

Double a given number by multiplying it by two.

RELATED LINKS

REMARKS

To see the examples, type: "Get-Help

/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/Get-DoubleValue.ps1 -Examples"

For more information, type: "Get-Help

/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/Get-DoubleValue.ps1 -Detailed"

For technical information, type: "Get-Help

/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/Get-DoubleValue.ps1 -Full"

And we can see our examples with the command Get-Help ./Get-DoubleValue.ps1 -Examples:

NAME

/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/Get-DoubleValue.ps1

SYNOPSIS

Double numbers.

-------------------------- EXAMPLE 1 --------------------------

PS>Get-DoubleValue -Number 5

10

-------------------------- EXAMPLE 2 --------------------------

PS>5,10,20 | Get-DoubleValue

10

20

40

Opinionated Naming Conventions

In most languages, naming conventions emerge from a mix of suggestions from the language maintainers and natural evolution in the community. Or maybe from a particularly note-worthy book like The C Programming Language by Kernighan & Ritchie.

Technically speaking PowerShell is no different, you can name functions/scripts anything you like, but you’ll be constantly harangued if you do! I’ve never come across a language that is so adamant about naming conventions, and I love it!

Before you come to naming anything of your own, notice that each and every standard command rigidly obeys a simple naming convention — commands and functions are named using the Verb-Noun pattern.

For those of you not up on your grammar terms, that means an action followed by a thing to be acted on. Or, putting it another way, command and function names tell you what they do to what!

There are no even vaguely enforced rules for the nouns (the whats), just a strong recommendation to be clear and consistent, but there is literally a list of approved verbs (the actions)!

The list of approved verbs is more than just a list, it also contains descriptions of how specific verbs should be interpreted, and there are disambiguations for verbs that could be easily confused. Until you get into the swing of things the subtle difference between similar verbs like Get and Read may not be obvious, but even if you never read any of the definitions or any of the helpful disambiguations, the rigorous consistency will seep in by osmosis anyway.

The end result of all this is that you can usually guess what the right command might be, or at least be close enough to search the documentation or the Internet to get you everything you need. For example, if you know you data to CSV format with ConvertTo-Csv command, you’d probably guess that you can convert to XML with ConvertTo-Xml, and to JSON with ConvertTo-Json.

While you’re just writing little scripts PowerShell will leave you alone and not start critiquing your names, but the moment you start grouping functions into modules PowerShell will start warning you each time you get it wrong! You can of course ignore and/or suppress the warnings, but if you do, don’t share you code with others, because that’ll hate you for your obstinance 🙂

My advice is very simple — get into the habit of always following the Verb-Noun pattern, and checking the docs each time to be sure you pick the right word until they become second nature to you.

Another way in which PowerShell is opinionated is in the casing of all names. While not enforced, PowerShell officially strongly recommends so-called PascalCase, that is to say the first letter of each word is capitalised, including the very first letter, and words are not separated by any symbols. All bult-in variables and functions, as well as all those in the many officially supported modules religiously use PascalCase. If you want to write PowerShell code that other PowerShell users will not find weird and unintuitive, you should adopt PascalCase in your code too!

A Robust Module Ecosystem

One final core feature in PowerShell is the notion of grouping related functions and variables into Modules. You can create your own modules easily by simply saving your variables and functions in files with .psm1 extensions, and once you do, you can import those variables and functions into your scripts with the Import-Module command or the more modern using statement.

For small scripts I don’t bother, but as soon as I start to build up a codebase with multiple scripts I start moving everything re-usable into a module file.

While writing your own modules is useful, the real power of the module system is in easily re-used other people’s code! Like NodeJS has NPM, PowerShell has the PowerShell Gallery.

Installing 3rd-party modules is trivially easy. For example out of the box PowerShell can read CSVs, JSON and XML with the Import-Csv, Import-Json & Import-Xml commands, but not Excel files. The community has of course provided a solution, so you can add support for Excel imports (and exports) with the simple command:

Install-Module -Name ImportExcel

Like with all similar repositories in all programming languages, always check the correct names of the modules you are trying to install from the project’s home page because attackers abuse obvious name guesses and typos to spread malware!

Because of Excel’s rigorous naming convention, you don’t even need to use the help system to figure out the command for importing from Excel once you have the module installed, it’s Import-Excel 🙂

A Very Basic Syntax Primer

PowerShell uses unix-style in-line comments, so anything following a # on a line is a comment. PowerShell also support multi-line comments by wrapping them between <# on a line by itself and #> on a line by itself.

# This entire line is a comment

Write-Host 'Hello World!' # just this end part of the line is a comment

<#

This is a

multi-line

comment

#>

Statements are separated by newline characters. If you absolutely need to put two commands on one line you can separate them with a ;, but this is strongly frowned upon, and all style guides agree that you should not end single-line commands with semicolons (just like in Bash!).

Variables have names pre-fixed with $, and they are created by assigning them a value.

Variables are collected in nested scopes, with each script/function getting its own scope.

# Define variables

$MyString = 'This is a string'

$MyInterpolatedString = "Double-quotes for interpolation: $MyString"

$MyEscapedString = "Escape caracter is `` (not \), this is a new line -> `nOn next line!"

$MyInt = 42

$MyDouble = 3.1415

$MyBoolean = $true

By default, variables have dynamic types, so they an hold a string one minute and number the next, but you can constrain them by pre-fixing them with a type, and when you do PowerShell will try to do automatic conversions as needed, but if it can’t, you’ll get an error :

[int]$MyNumber = 4

$MyNumber = 5.6

Write-Host $MyNumber # outputs 6!

$MyNumber = 'Hello World!' # throws an error

PowerShell supports arrays with pretty intuitive syntax:

# creating arrays

$MyArray1 = @() # an empty array

$MyArray2 = @(42, 'Hello World!', $false) # an array with three items

# getting their length

Write-Host $MyArray1.Count # outputs 0

Write-Host $MyArray2.Count # outputs 3

# access elements

Write-Host $MyArray2[0] # outputs first element, i.e. 42

Write-Host $MyArray2[1] # outputs second element, i.e. Hello World!

Write-Host $MyArray2[-1] # outputs last element, i.e. False

# update elements

$MyArray2[2] = $true

# add elements

$MyArray2 += 'a fourth element'

# looping over elements

foreach ($Item in $MyArray2) {

Write-Host $Item

}

PowerShell also supports what we call dictionaries, i.e. name-value pairs, but it calls them hashtables:

# creating hashtables

$MyDictionary1 = @{} # an empty hashtable

$MyDictionary2 = @{

MyFirstKey = 42

MySecondKey = 'Hello World!'

MyThirdKey = $false

}

# getting the number of key-value pairs

Write-Host $MyDictionary1.Count # outputs 0

Write-Host $MyDictionary2.Count # outputs 3

# accessing values

Write-Host $MyDictionary2.MyFirstKey

Write-Host $MyDictionary2['MySecondKey']

# accessing keys

$MyDictionary2Keys = $MyDictionary2.Keys

# updating keys

$MyDictionary2.MySecondKey = 'Hello again World!'

$MyDictionary2['MyThirdKey'] = $true

# Looping over hashtables

foreach ($Key in $MyDictionary2.Keys) {

Write-Host "$Key = $($MyDictionary2[$Key])"

}

PowerShell also provides conditionals using standard if/else syntax. The thing to be aware of is that all the comparison operators are Bash-like -blah operators, not the symbolic operators like <, == etc. JavaScript uses.

The most important comparisons are:

| Operator | Comparison |

|---|---|

-eq |

Default equality, which is case-insensitive |

-ieq |

Explicitly case-insensitive equity |

-ceq |

Case-sensitive equality |

-like |

CLI-style wild-cards like '*.csv' |

-match |

PCRE-style regular expression matching like '\d+' |

-lt |

Less than |

-gt |

Greater than |

-le |

Less than or equal to |

-ge |

Greater than or equal to |

Putting it all together:

$TestString = 'Hello World!'

$TestNumber = 42

# default string equality (case insensitive!)

if ($TestString -eq 'hello world!') {

Write-Host 'Yes!'

} else {

Write-Host 'no'

}

# ouptuts Yes!

# CLI-style like

if ($TestString -like '*world*') {

Write-Host 'Yes!'

} else {

Write-Host 'no'

}

# ouptuts Yes!

# default numeric equality

if ($TestNumber -eq 42) {

Write-Host 'Yes!'

} else {

Write-Host 'no'

}

# ouptuts Yes!

Next Steps

If I’ve successfully whet your appetite, the next step would be spend a little time with the documentation. One of the best things about PowerShell is how well documented it is, and one of the worst things about PowerShell is how well documented it is 🙂 What I mean by that is that you actually need to take a little time to learn your way around the documentation.

First and foremost, bookmark the landing page: learn.microsoft.com/…

Once you’re there, notice the side bar has a drop-down where you can specific the version of PowerShell you’re using. It will default to the current release, as will Home Brew, so that should be right, but if you’re getting information that doesn’t make sense, check!

Secondly, notice the search box, this is very much your friend. Just start typing and the matching articles will appear underneath.

Finally, I want to draw your attention to two important sections:

- The Learning PowerShell section is very much a beginner’s friend. If you’re very new to the whole idea, the PowerShell 101 sub-section is probably the place to start, but if you’re more of a power user in general who wants to dive straight in, the Deep Dives subsection is great for actually understanding how PowerShell implements core concepts like arrays, etc.

- The Reference section is where you’ll find the traditional API-style docs you’ll probably want most. By far the most important sub-section in there is Microsoft.PowerShell.Core. I want to specifically all out the articles in the About sub-sub section in the Microsoft.PowerShell.Core sub-section. The most important sub-section after Microsoft.PowerShell.Core is Microsoft.PowerShell.Utility.

As with all coding adventures, it really helps to have a pet project, so some kind of problem to be solved that’s not so urgent you’ll be under pressure.

Final Thoughts & 2025 Plans

This TidBit was intended to stand alone, but was also very much a trial balloon. At the end of the matching podcast episode for the first half of this Tidbit we asked the community to let us know if there would be interest in the main PBS series covering PowerShell in depth like we did Bash. The community spoke quickly and loudly with a resounding YES!

That nearly brings us to the question of what we’ll be doing in the main PBS series this year. Our thinking is that 2025 will be a game of two halves — we’ll start by exploring GitHub pages, then we’ll do the requested deep dive on PowerShell.

We’ll have the usually introductory instalment to set the scene properly, but to whet your appetite a little, these are some of the reason you may want to join us for the GitHub Pages arc:

- Learn how to get some free and surprisingly powerful web hosting!

- Understand how this series gets transformed from a collection of Markdown files in a Git repo to a beautiful website entirely automatically each time a change is pushed.

- Learn how to deploy a full-feature content management system without needing database hosting or installing any server-side apps that need to be patched and secured.

- Learn how to customise Bootstrap in order to unlock it’s full potential. Did you ever notice that both this site and Bootstrap’s own website are built using Bootstrap, and yet, they look nothing like the web apps we’ve been building with Bootstrap in this series? That’s because we’ve ignored about half of Bootrap’s feature set — as it’s name implies, it is designed to from the ground up to be customisable and extensible!

- In the process of learning how to customise Bootstrap in the way its developers intended we’ll meet a whole new web technology — CSS pre-processors, specifically, the most popular one of them all, Sass.

While we’re exploring GitHub pages I’ll be mapping out the best way to tell the PowerShell story.