PBS 76 of X: AJAX with jQuery

Having laid a very strong foundation in the previous instalment, we’re now ready to learn how to make HTTP requests with JavaScript using a technique known as AJAX.

We’ll start our journey into AJAX using more traditional JavaScript techniques, i.e. we’ll use callbacks to handle HTTP responses. As we’ll discover, this works very well for single AJAX requests, but the model really starts to get complicated when you have multiple interdependent requests. We won’t complicate things in this instalment though — we’ll start with just simple stand-alone requests this time.

You can download this instalment’s ZIP file here or here on GitHub.

Matching Podcast Episode 590

Listen along to this instalment on episode 590 of the Chit Chat Across the Pond Podcast

You can also Download the MP3

Before we Get Started — A Note on the Bootstrap Grid and Bootstrap Flex Utilities

While working on the challenge set back in instalment 74, a few listeners ran into the same issue — confusion between the Bootstrap Grid classes, specifically the col classes, and the Bootstrap Flex Utility classes, specifically justify-content-around.

The way I think of this is that the grid and the flex utilities are different species. You use the grid classes to lay out the big chunks of your page, and you use the flex classes to turn a single tag into a flex container and control how the flex items within it behave. If you find yourself using a flex utility class like justify-content-around on a tag that doesn’t also have the class d-flex, you need to stop and think, because you’re in dangerous territory.

What complicates this a little bit, and why it’s dangerous territory rather than simply categorically wrong, is that there is one context where the grid and the flex utilities meet and can live together in harmony — the grid row.

The reason for this is that under the hood, Bootstrap implements grid rows as flex containers (they get the CSS attribute display: flex).

So, my final advice is this: if you’re using a Bootstrap Flex utility class in a tag that does not also have the Bootstrap class d-flex or row, you’re probably doing something wrong.

PBS 74 Challenge Solution

Back in instalment 74, I set a challenge to use Mustache templates to build a flexbox-based contacts listing using a given file as a starting point.

In PBS 75, I offered a tip to help with the challenge. In that tip I suggested building the template before building your view object. So I’m going to follow my own advice in this sample solution.

But before starting any real work, I needed to do a little housekeeping. I started by updating the jumbotron text to better describe the page:

<header class="container mt-5">

<div class="jumbotron">

<h1 class="display-4">Contact the Hosts<br><small class="text-muted">PBS 74 Challenge</small></h1>

<p class="lead">Bart's sample solution to the challenge set in <a href="https://www.bartbusschots.ie/s/2019/03/24/pbs-74-of-x-more-mustaches/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">instalment 74</a> of the <a href="https://bartb.ie/pbs" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Programming by Stealth series</a>.</p>

</div>

</header>

Next, I updated the main body of the page to include a placeholder into which the contact cards can later be added:

<main class="container mb-5">

<div class="row mb-4">

<div class="col">

<p>You can use the links below to contact the hosts of the Programming by Stealth podcast series.</p>

<div class="container">

<div class="row" id="contact_cards"></div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</main>

I’ve highlighted the node into which I’ll be injecting the contact cards. Note that it’s a Bootstrap grid row, and that it has the ID contact_cards. This means that the individual contact cards must be Bootstrap grid columns.

Step 1 — Build a Basic Template & any Needed Partials

At this point I knew where in the document I’d be injecting my contact cards. So I could now do a first pass at my template. In keeping with Bootstrap best practices, I started by building a template aimed at the smallest breakpoint (xs):

<!-- The Mustache Template for a Contact Card -->

<script type="text/html" id="contact_card_tpl">

<nav class="col-12 mb-3 p-2">

<h1 class="h5">Contact {{name.first}}</h1>

<div class="d-flex flex-column">

{{# contactMethods}}

<div class="p-1">

<span class="d-inline-block" style="width: 1.5em;">{{> icon}}</span>

<span>{{value}}</span>

</div>

{{/ contactMethods}}

</div>

</nav>

</script>

Some key points to note:

- Because these contact cards are likely to end up being big collections of links, I felt

<nav>was the most appropriate HTML semantic tag to use. - The

<nav>is a full-width Bootstrap grid column (col-12), has medium bottom margin (mb-3), and a medium small padding (p-2). - Each card consists of two top-level elements:

- A top-level title (

<h1>) containing the person’s first name{{{name.first}}}. Semantically this is the top level heading within the<nav>, so<h1>is the appropriate tag. But it will look much too big, so note the use of Bootstrap’sh5utility tag to render it smaller. - A flex container (

d-flex) containing a Mustache loop over an array namedcontactMethods. The assignment explicitly required Bootstrap’s flex utilities be used. By default flex boxes display horizontally, but they can also stack items vertically. That’s a much better fit here, hence the use offlex-column.

- A top-level title (

- Each contact item within the card is represented by a

div. Remember that, by virtue of being direct children of a flex container, these<div>s are flex items. I gave each contact item a small amount of padding (p1). - Each contact item contains two

spans, one for the icon, and one for the text ({{value}}). Note that the icon is rendered with a partial namedicon. - To ensure all the text aligns nicely, I converted the

spans containing the icons into inline blocks withd-inline-block, and gave them a fixed width of one and a half characters with the inline style attributestyle="width: 1.5em;". The reason for converting thespans from their defaultinlinedisplay toinline-blockis so that they have awidthproperty.

Finally, there is a little more markup to look at in the definition of the icon partial:

// define any needed partials

const partials = {

icon: '<i class="{{{icon.classes}}}" title="{{{icon.title}}}" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="sr-only">{{{icon.title}}}</span>'

};

Note that this partial makes use of a view variable named icon which is an object containing at least two keys:

classes- The CSS classes for the Font Awesome icon.

title- The text to use as the tooltip for sighted visitors, and the alternative text for screen readers.

The icon consists of two parts; an <i> tag forms the visible icon and is hidden from screen readers with aria-hidden="true", while a <span> provides a label that is visible only to screen readers with the sr-only class.

The template and partials together define the form of the view objects will need to take. I did not write my templates to match a pre-existing view. I wrote my template so it reads well, and then that determined the shape of the view objects I needed to build.

This is the structure imposed by my template and partials:

{

name: { // an object

first: 'A FIRST NAME' // e.g. 'Allison'

},

contactMethods: [ // an array of objects, one for each contact method

// …

{

name: 'A CONTACT METHOD NAME', // e.g. 'twitter'

value: 'THE VALUE FOR THE CONTACT METHOD' // e.g. 'podfeet'

icon: { // an object

classes: 'FONT AWESOME CLASSES', // e.g. 'fab fa-twitter'

title: 'A TITLE FOR ACCESSABILITY', // e.g. 'twitter'

}

},

// …

]

}

Step 2 — Build the View Objects from the JSON Data

To actually see the template and partials in action, I now needed to write a document ready handler to perform the following four tasks:

- Read the template from the

<script>tag within which it is defined. - Read and parse the JSON data from the

<script>tag within which it is defined. - Build a view object for each person matching the structure above.

- Use Mustache to render the contact cards and inject them into the page using jQuery.

// document ready handler

$(function(){

// fetch the contact card template

const contactTpl = $('#contact_card_tpl').html();

// fetch the data from the json string

data = JSON.parse($('#pbs74_view_data').text());

// build the view objects

const people = [];

for(const uname of Object.keys(data.people).sort()){

const person = {

name: data.people[uname].name,

contactMethods: []

};

for(const contactName of Object.keys(data.people[uname].contact).sort()){

const contactVal = data.people[uname].contact[contactName];

person.contactMethods.push({

name: contactName,

value: contactVal,

icon: {

classes: data.contactIcons[contactName],

title: contactName

}

});

}

people.push(person);

}

//console.log('generated view objects:', people);

//window.alert('generated view objects:\n' + JSON.stringify(people, null, 2));

// render the contact cards

const $contactCardHolder = $('#contact_cards');

for(const person of people){

$contactCardHolder.append(Mustache.render(

contactTpl, // the template

person, // the view

partials // the partials

));

}

});

The loading of the template and the JSON object are by-the-book, so they are not worth dwelling on.

It’s worth noting that, to avoid code duplication, I chose to put my call to Mustache.render() inside a loop, and to facilitate that I stored my view objects in an array named people.

The interesting part of this handler is the building of the view objects. So let’s dig in a little deeper there.

Note that you might find it easier to follow along if you can see the structure of the view objects generated. You’ll notice two commented-out lines in the code — you can uncomment one to render the view objects to the console, or the other to render them as a popup (or both).

Remember that my template and partials have predetermined the structure the view objects will have to take, so we know what we need. We also know what we have in the JSON data, and the two align. The only task remaining was to write the code to construct the needed ‘from’ objects from the data in the loaded data object.

My code makes use of three JavaScript features we’ve used earlier in this series — the Object.keys() function (introduced back in instalment 17), the Array prototype’s .sort() function (introduced in instalment 18), and the for...of loop (introduced in instalment 45).

As a quick reminder:

Object.keys()returns an object’s keys as an array of strings.- When you call

.sort()on an array, a new array is returned with the values sorted lexically. - A

for...ofloop can be used to loop over an array.

You can follow along by enabling the JavaScript console on the file pbs74-challenge-solution/basic.html in this instalment’s ZIP. To make it easier to do this, I made sure to define the variable data in the global scope. That way, it can be accessed from the console.

We can access the object defining the data about Allison and Bart at data.people. This object is indexed by two keys (allison & bart). We can get those keys with Object.keys(data.people). For good measure we should sort them, hence the for...of loop iterating over Object.keys(data.people).sort().

Given this simple for...of loop, we can log all the keys in the data.people object in alphabetical order (try it in the JavaScript console):

for(const uname of Object.keys(data.people).sort()){

console.log(uname);

}

Note that within this loop we can access the relevant person’s details via data.people[uname]. For example the following loop will log both people’s full names (try it in the JavaScript console):

for(const uname of Object.keys(data.people).sort()){

console.log(`${data.people[uname].name.first} ${data.people[uname].name.last}`);

}

So, my code builds the needed array of view objects by looping over the keys in data.people. Within the loop it builds an object for each person named person and, when that object is complete, adds it to the end of the people array.

My code starts to build each person object by creating an object with just the two needed top-level keys (name, and contactMethods):

const person = {

name: data.people[uname].name,

contactMethods: []

};

At this point person.contactMethods is an empty array. So the next task is to build the needed objects for each contact method and add them into the array.

As a reminder, each contact method object needs to have the following form (determined by my template and partials):

{

name: 'A CONTACT METHOD NAME', // e.g. 'twitter'

value: 'THE VALUE FOR THE CONTACT METHOD' // e.g. 'podfeet'

icon: { // an object

classes: 'FONT AWESOME CLASSES', // e.g. 'fab fa-twitter'

title: 'A TITLE FOR ACCESSABILITY', // e.g. 'twitter'

}

}

To build one of these objects for each contact method, I used another for...of loop.

If you look at the JSON object, you’ll see that, within each person, there’s an object named contact which represents each piece of contact information as a name-value pair. Again, we’ll need to make use of Object.keys() to get at the data we need:

for(const contactName of Object.keys(data.people[uname].contact).sort()){

const contactVal = data.people[uname].contact[contactName];

person.contactMethods.push({

name: contactName,

value: contactVal,

icon: {

classes: data.contactIcons[contactName],

title: contactName

}

});

}

The important subtlety to note is that the keys in each person’s contact object match the keys in data.contactIcons. Hence it’s possible to use data.conctactIcons as a lookup table to get the CSS classes for each piece of contact information (data.contactIcons[contactName]).

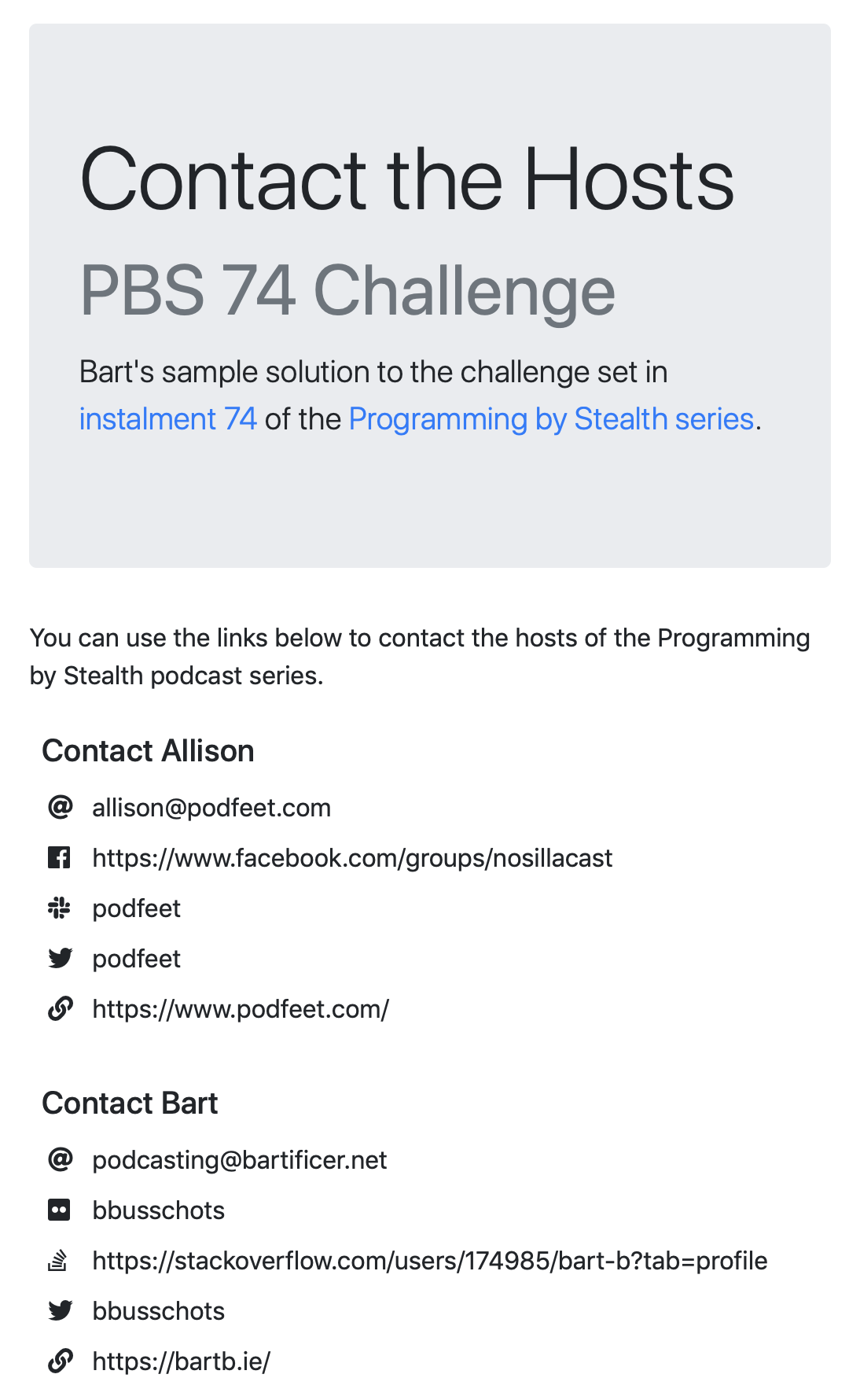

Well, that was a lot of work, but we can finally see our first draft of our contact card:

Step 3 — Tweak the Template

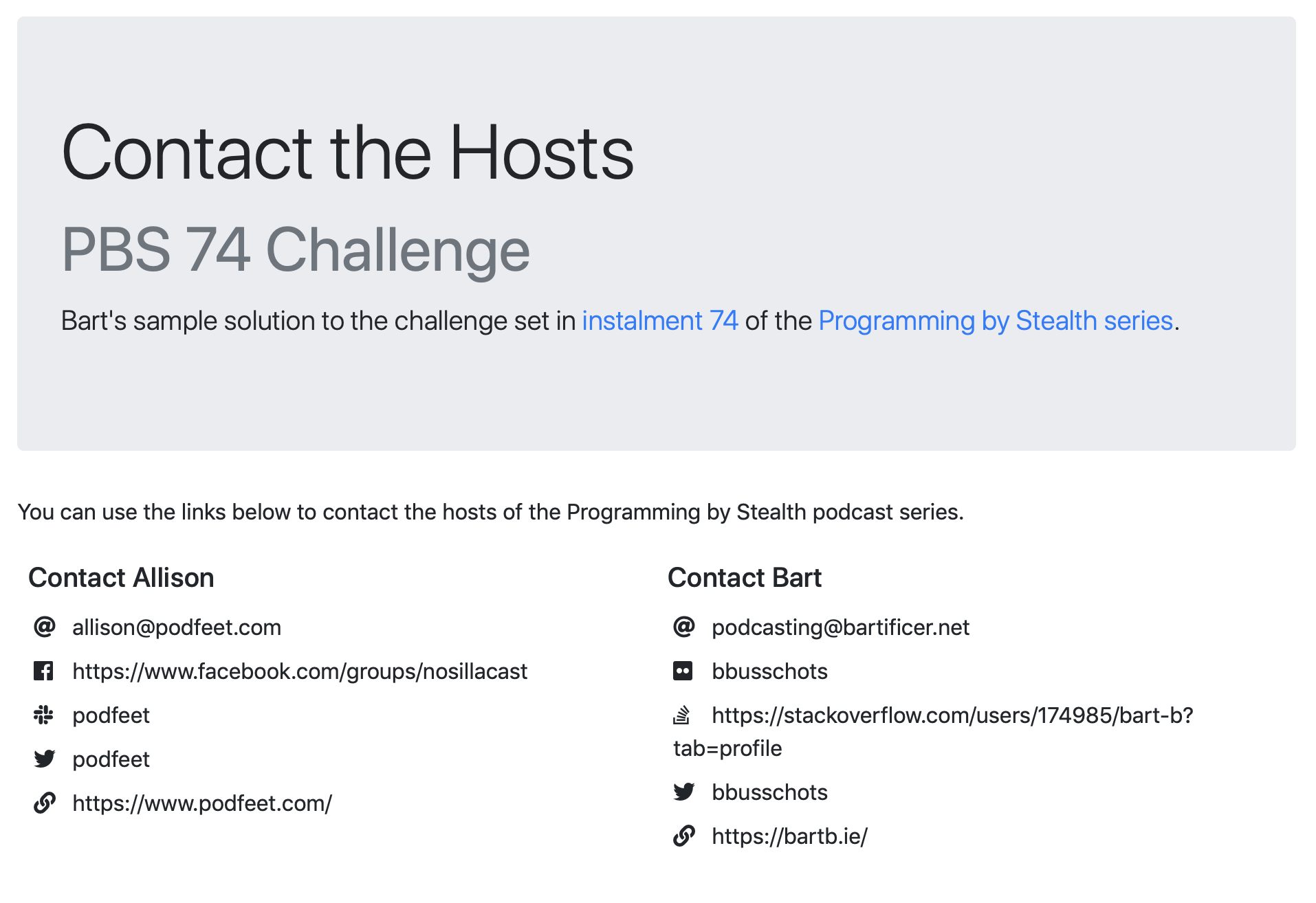

That looks fine at the smallest break point, but it does start to look a bit ridiculous as larger breakpoints. So, I needed to allow the cards to go side-by-side from lg up. I did that by simply adding col-lg-6 to the <nav> in the template.

That actually worked pretty well:

That did leave the very silly situation where there were things displayed that are obviously links, but were not actually clickable. I felt I couldn’t leave things there, so I made another tweak to my code.

My first step was expand my view generation code a little and add a test to check whether or not the value for a given contact method was a URL or not. For example 'podfeet' is not a URL, but 'https://www.podfeet.com' is.

I chose to use a regular expression in combination with the .match() function from the String prototype (relevant docs available here).

const valIsURL = contactVal.match(/^http(s)?[:]\/\//);

The RE takes a little unpacking. The ^ means start of string, () defines a group, in this case just the letter s. That group is made optional with the addition of the ? which means zero or one of. This is how my RE supports both http:// and https:// URLs. The character class [:] simply matches the : symbol. I had to remember to escape the / character with \/.

Next I defined a partial for rendering a link:

const partials = {

icon: '<i class="{{{icon.classes}}}" title="{{{icon.title}}}" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="sr-only">{{{icon.title}}}</span>',

link: '<a href="{{{link.url}}}" target="_blank" rel="noopener">{{link.text}}</a>'

};

This partial imposes more structure on the view objects — the links must be added to the view as object of the form:

{

url: 'https://SOMEDOMAN.TLD/…',

text: 'THE VISIBLE LINK TEXT'

}

With the partial created and named (link), I could update my template to make use of it. This updated template only renders a clickable link when the contact method object contains a link object:

<!-- The Mustache Template for a Contact Card -->

<script type="text/html" id="contact_card_tpl">

<nav class="col-12 col-lg-6 mb-3 p-2">

<h1 class="h5">Contact {{name.first}}</h1>

<div class="d-flex flex-column">

{{# contactMethods}}

<div class="p-1">

<span class="d-inline-block" style="width: 1.5em;">{{> icon}}</span>

{{# link}}

<span>{{> link}}</span>

{{/ link}}

{{^ link}}

<span>{{value}}</span>

{{/ link}}

</div>

{{/ contactMethods}}

</div>

</nav>

</script>

Finally, I updated my view creation code to inject the needed link objects when the RE matched the value for the contact method being processed.:

// build the view objects

const people = [];

for(const uname of Object.keys(data.people).sort()){

const person = {

name: data.people[uname].name,

contactMethods: []

};

for(const contactName of Object.keys(data.people[uname].contact).sort()){

const contactVal = data.people[uname].contact[contactName];

const valIsURL = contactVal.match(/^http(s)?[:]\/\//);

let link = false;

if(valIsURL){

link = {

url: contactVal,

text: contactVal

};

}

person.contactMethods.push({

name: contactName,

value: contactVal,

icon: {

classes: data.contactIcons[contactName],

title: contactName

},

link: link

});

}

people.push(person);

//console.log('generated view objects:', people);

//window.alert('generated view objects:\n' + JSON.stringify(people, null, 2));

}

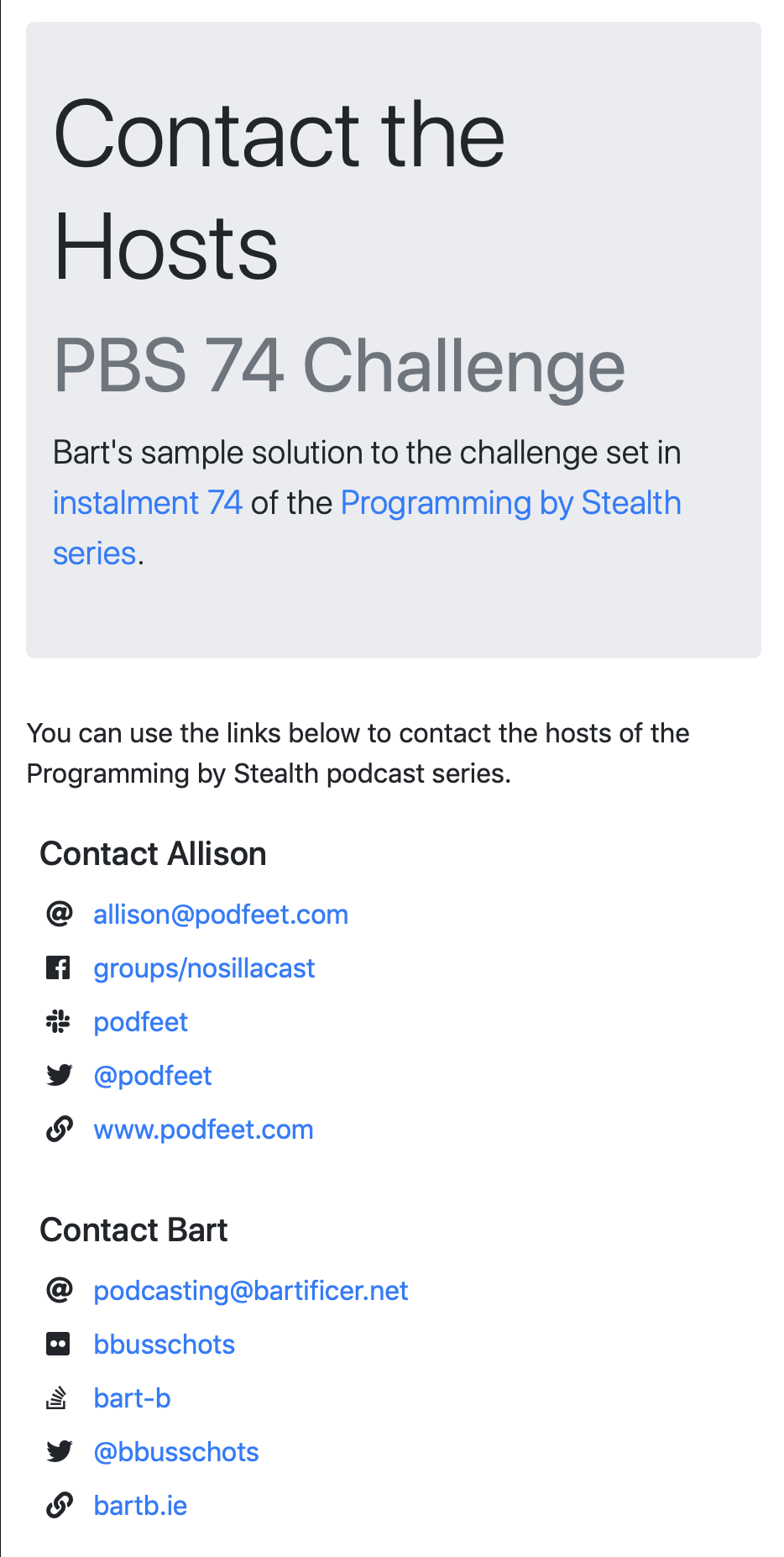

And that’s that! This sample solution now meets all the criteria set out in the challenge, so full marks!

Optional Extra Credit — Advanced Challenge Solution

I got a little carried away, and wasn’t happy to leave things there. I went on to create a more advanced sample solution that addressed two shortcomings in my original solution:

- I wanted every contact item to become a link, and to have link text that’s more appropriate for the relevant contact type. For example I wanted the twitter name to be rendered with an

@prefixed, and to be a link to the actual Twitter profile. - I wanted a nicer layout at larger sizes — a horizontal arrangement of large icons with text and a link centred below them.

Basically, I wanted to achieve this:

Extra Credit 1 — Data Transformer Lookups

For all the contact methods, there is actually enough information provided to create a nice link. We just need to transform what we have into what we need.

We could write a separate function for each contact type, name it, and then have a great big if–else–if or case statement to select the correct function, but the code would be extremely unwieldy!

How could we do it better? We could adapt the lookup table idea used in data.contactIcons. Instead of mapping the names of the contact items (twitter etc.) to strings, we could map them to anonymous functions. These will be tiny little functions, so they can be most easily written as ES6 fat arrow (or just arrow) functions.

In some cases we won’t need to do any transformation at all. So to save code duplication I first created a function to simply return whatever is passed:

const passthrough = function(val){

return val;

};

We can rewrite this traditional function as an arrow function like so:

const passthrough = (val)=>{ return val; };

Many of these little transformation functions will depend on using regular expressions with the .replace() function from the String prototype (docs available here). This function takes two arguments, a regular expression to match, and a replacement string. The replacement string can insert capture groups from the RE by using the special strings $1, $2 etc..

As a practical example, let’s look at a function for transforming the Stack Overflow URL into a stack overflow username. The URLs take the form https://stackoverflow.com/users/USER_ID/USERNAME?tab=profile where USER_ID is a number, and USERNAME is the text we want to extract. For example, https://stackoverflow.com/users/174985/bart-b?tab=profile has the user ID 174985 and the username bart-b.

This is the relevant arrow function:

(val)=>{ return val.replace(/^http(?:s)?[:]\/\/stackoverflow[.]com\/users\/\d+\/(.+)[?]tab=profile$/, '$1'); }

A lot to absorb, but let’s step through it like we did with the .match() RE earlier.

Notice the first part of the RE is identical to what we had before. It matches the start of the string followed by http:// or https:// using a non-capturing group to make the s optional. This is important, because it means the s is not in $1. If we’d just used regular parentheses, we’d have created a capturing group. Then the matched value, 's' or an empty string in this case, would have been stored in $1.

We then match the string 'stackoverflow.com/users/', remembering to escape the / characters with \/, and using the character class [.] to represent an actual period symbol. Remember, were it not in the character class, the . would mean ‘any single character’. Then we match one or more digits followed by a / with /\d+\/. Next comes the really important part — the capture group for the username: (.+). Remember, . means ‘any character’, + means ‘one or more’, and parentheses create a capture group. So we are capturing one or more of any character, and storing that value in the first capture group, which we can access in the replacement string as $1. We don’t want to include the trailing ?tab=profile in the capture group. So we have to match that outside the parentheses. Because ? means ‘zero or one’, I use the character class [?] to match the actual question mark symbol, and $ means 'end of string'. Finally, the replacement string (second argument to .replace()) is simply '$1', i.e. the contents of the first (and only) capture group.

Putting it all together I created two lookup tables, one defining functions for transforming the raw values (the keys from data.people.allison.contact and data.people.bart.contact) into URLs, and one for transforming them into meaningful text for the links. I added my lookup tables into the data object for easy access:

// inject helper functions for generating pretty values

// and URLs for each contact type into the data structure

const passthrough = (val)=>{ return val; };

data.prettyValueGenerators = {

"email": passthrough,

"facebook": (val)=>{ return val.replace(/^http(?:s)?[:]\/\/www.facebook.com\//, ''); },

"flickr": passthrough,

"slack": passthrough,

"stackOverflow": (val)=>{ return val.replace(/^http(?:s)?[:]\/\/stackoverflow[.]com\/users\/\d+\/(.+)[?]tab=profile$/, '$1'); },

"twitter": (val)=>{ return `@${val}`; },

"url": (val)=>{ return val.replace(/^http(?:s)?[:]\/\//, '').replace(/\/$/, ''); }

};

data.urlGenerators = {

"email": (val)=>{ return `mailto:${val}`; },

"facebook": passthrough,

"flickr": (val)=>{ return `https://flickr.com/people/${val}`; },

"slack": (val)=>{ return `https://${val}.slack.com/`; },

"stackOverflow": passthrough,

"twitter": (val)=>{ return `https://twitter.com/${val}`; },

"url": passthrough

};

You can see these functions in action by opening the JavaScript console on pbs74-challenge-solution/advanced.html from the ZIP file and entering:

data.prettyValueGenerators.twitter('podfeet');

data.urlGenerators.twitter('podfeet');

We now know that our view will always have link information within it. So we can remove the condition where there is no link from the template and simply assume there will always be one. The <span> containing the visible text becomes just {{> link}}.

We also need to update our code for generating the view objects to use our new lookup tables:

// build the view objects

const people = [];

for(const uname of Object.keys(data.people).sort()){

const person = {

name: data.people[uname].name,

contactMethods: []

};

for(const contactName of Object.keys(data.people[uname].contact).sort()){

const contactVal = data.people[uname].contact[contactName];

person.contactMethods.push({

name: contactName,

value: contactVal,

link: {

url: data.urlGenerators[contactName](contactVal),

text: data.prettyValueGenerators[contactName](contactVal)

},

icon: {

classes: data.contactIcons[contactName],

title: contactName

}

});

}

people.push(person);

//console.log('generated view objects:', people);

//window.alert('generated view objects:\n' + JSON.stringify(people, null, 2));

}

That takes care of my first desire — nicer links.

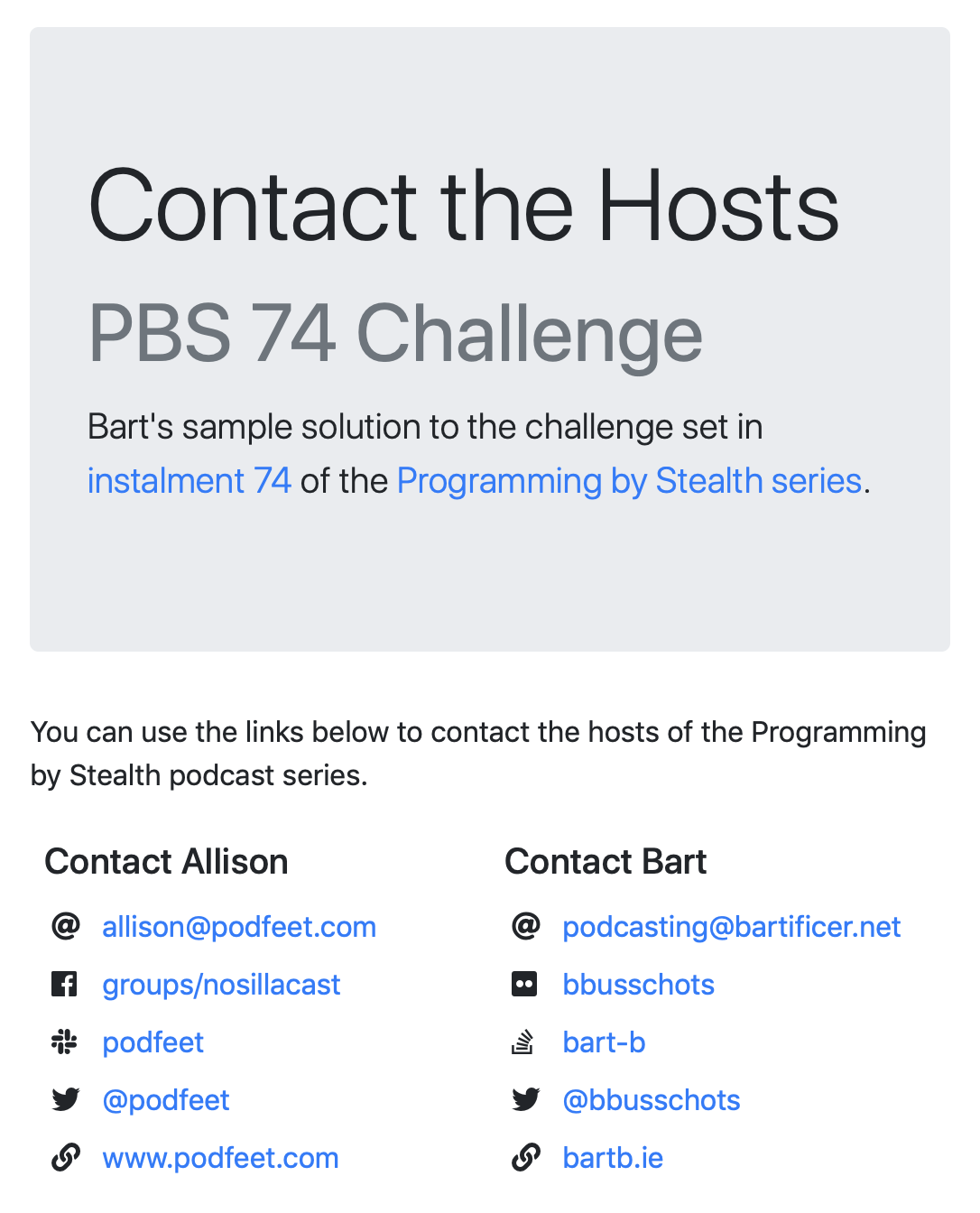

Extra Credit 2 — A More Responsive Layout

Now that the text for each contact type has been shortened, it becomes much more practical to have them side-by-side instead of one under the other at larger screen sizes. For that to look good, the icons need to become much bigger, and be located above the text.

Before starting that though, the shorter text also means we can move the two cards side-by-side even at the sm breakpoint. So let’s start by replacing col-lg-6 with col-sm-6.

OK, now let’s move on to making the side-by-side icons from the md breakpoint up.

Firstly, for side-by-side to work, each card needs to become full width again at the md breakpoint. So we need to add col-md-12, giving us col-12 col-sm-6 col-md-12.

Secondly, since there are no responsive size classes, the easiest way to achieve different icon sizes at different breakpoints is with separate icons, a big one and a small one, one of which is always hidden.

We want our existing small icon to be visible for breakpoints sx and sm, but be hidden from md up. So we start by adding d-md-none to that span:

<span class="d-inline-block d-md-none" style="width: 1.5em;">{{> icon}}</span>

Next we add a new larger icon which should be hidden for breakpoints xs and sm, then become visible from md up:

<div class="d-none d-md-block text-center h1">

{{> icon}}

</div>

Note that I’ve made the icon large using the h1 Bootstrap utility class.

Also note that the existence of the icon partial has saved me from some code duplication.

We’re now ready to make the flex container switch from vertical stacking to horizontal stacking from the md breakpoint up. We do this by adding the Bootstrap flex utility class flex-md-row. To allow any icons with long text to flow onto a possible extra row if needed, we add flex-md-wrap. To align the items nicely, we add justify-content-md-between.

We’re almost there, but we still need to centre the icons and text, and also centre the heading containing the person’s name. We can do all this with the responsive Bootstrap utility class text-md-center.

Putting it all together, my updated template becomes:

<!-- The Mustache Template for a Contact Card -->

<script type="text/html" id="contact_card_tpl">

<nav class="col-12 col-sm-6 col-md-12 mb-3 p-2">

<h1 class="h5 text-md-center">Contact {{name.first}}</h1>

<div class="d-flex flex-column flex-md-row flex-md-wrap justify-content-md-between">

{{# contactMethods}}

<div class="p-1">

<div class="d-none d-md-block text-center h1">

{{> icon}}

</div>

<span class="d-inline-block d-md-none" style="width: 1.5em;">{{> icon}}</span>

<span class="d-md-block text-md-center">{{> link}}</span>

</div>

{{/ contactMethods}}

</div>

</nav>

</script>

AJAX — Asynchronous HTTP Requests with JavaScript

AJAX is technically an acronym: Asynchronous JavaScript and XML. Don’t get too hung up on this though. The XML part isn’t really relevant to our experience of actually using AJAX as a JavaScript developer. The two words within that backronym that really do matter are Asynchronous and JavaScript.

The JavaScript part is obvious, but the asynchronous part may not be.

When a chunk of code executes synchronously, each statement happens in turn, one after the other, starting with the first and ending with the last. Synchronously executing code always happens in the same order, one line after the next line, after the next. No two lines of synchronous code are ever executing at the same time.

Synchronous code is easy to write, easy to understand, and makes up the vast bulk of our code. However, there are times when synchronicity becomes problematic. Network IO (input/output) is a classic example of this. Another term for describing synchronous IO is blocking IO. Simply put, in computer time, it takes an absolute eon to get a response from a web server. If you execute such requests synchronously then they block execution of the rest of your code while they wait. If we used blocking IO for HTTP requests in JavaScript, we’d end up with utterly unusable web apps that repeatedly hang for seconds at a time! Simply put, synchronous network IO does not work!

If we can’t do things synchronously, then we have to do them asynchronously, or, to put it another way, we have to use non-blocking network IO when making using JavaScript to make HTTP requests.

With asynchronous network IO, execution doesn’t wait when an HTTP request is made. Instead, it continues to the next line of code as soon as the request is started. We need to use some kind of event handler to react when the request finally finishes and we have a response from the server.

The original mechanism for asynchronous programming in JavaScript is callbacks. In fact, we’ve been doing asynchronous programming within this series for a long time. All event handlers are asynchronous, as are all timeouts and intervals.

More recent versions of JavaScript have completely reimagined asynchronous programming through the adoption of so-called promises, and the async and await keywords.

Because we’re already familiar with callbacks, we’ll start our exploration of AJAX using this older approach, but we’ll shortly use AJAX as a reason to learn about promises. What will become apparent soon is that callbacks come with some serious limitations, so much so that you’ll often hear JavaScript developers complain about being stuck in callback hell! Promises were invented to free developers from callback hell. So once we’ve spent a little time there, we’ll be well motivated to learn all about promises 🙂

So, in summary, AJAX is nothing more or less than a mechanism for asynchronously making HTTP requests with JavaScript.

The Same Origin Policy

For extremely sound security reasons, browsers prevent JavaScript from making AJAX requests to URLs that don’t share the same HTTP scheme, domain, and port number as the page the code is executing on. That sounds complicated, but what it means in practice is that you can’t use AJAX to fetch data from an http:// URL if the JavaScript making the request is at an https:// url, and vice-versa. It also means that, if your JavaScript is running in a page served from port 80, it can’t make an AJAX call to port 8080. Finally, it means JavaScript running on bart.ie can’t make AJAX calls to URLs on podfeet.com. Do note that sub-domains are OK, so code on bartb.ie could make an AJAX call to a URL at scripts.bartb.ie.

In the past the block on cross-origin AJAX was absolute, but that is not true anymore. There are legitimate reasons for a developer to wish to make a web service on one domain available from another. Modern browsers now all support a mechanism whereby the owner of a web server can choose to allow AJAX queries from other domains access their URLs. The mechanism is known as CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing), and relies on the server including the HTTP response header Access-Control-Allow-Origin to specify the domains from which cross-origin AJAX requests should be permitted by the browser. Wildcards are allowed, so the author of a web service designed to be used from anywhere on the internet can configure their server to send the header Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *.

Also for security reasons, modern browsers will not allow JavaScript running on a page with a file:// URL to make any AJAX queries at all. For this reason you’ll need to use your local web server for all our AJAX examples. That way the URL will be http://localhost… rather than file://….

jQuery’s $.ajax() Function

Important Note: there are two flavours of jQuery, the full-featured flavour, and the slim flavour. The slim flavour contains only the core jQuery features, and does not include some of jQuery’s more advanced features, including AJAX support! So, if you want to use AJAX with jQuery, make sure the version you are using does not contain slim in the URL/filename. When fetching the jQuery include code from jQuery’s CDN (https://code.jquery.com/), the flavour you want is the one labeled minified.

Because we’re familiar with jQuery, and have been using it throughout this series, we’ll be using jQuery’s AJAX features to make our HTTP requests. As with everything else jQuery does, the same functionality is available in raw JavaScript. I just don’t find the native implementation to be as nice to use.

jQuery provides multiple AJAX functions, but under the hood, all of them are just wrappers for jQuery’s primary AJAX function, $.ajax(). Until you understand $.ajax(), it won’t be clear what shortcuts/conveniences the other functions provide. So we’ll start our exploration with $.ajax().

As with so many jQuery functions, the $.ajax() function can be called with a number of different combinations of arguments. We’ll be using the function in its simplest single-argument form. The single argument we’ll be passing is a dictionary (plain object) of options.

Note that $.ajax() is an extremely feature-rich function that supports an impressive array of options. So as usual, our exploration of this function won’t be exhaustive. To see everything this function can do, check out the relevant page on jQuery’s documentation site.

$.ajax() returns a jqXHR object. This is a special kind of object jQuery uses to represent both the HTTP request and response associated with an AJAX call. This is an extremely powerful object that bundles an impressive array of features. For now, we’re just interested in the following few properties and functions:

.status- The HTTP response status code as a number, e.g.

404. .statusText- The full HTTP response status code as a string, e.g.

'404 Not Found'. .getAllResponseHeaders()- Returns all HTTP response headers as a string, one header per line or

nullif the response has not been received from the server yet. .getResponseHeader(headerName)- Returns the value for the given HTTP response header as a string, or

nullif the response has not been received from the server yet, or if the response did not contain the specified header.

Again, just a reminder that the above is just a tiny subset of the features provided by jqXHR objects. You can get all the details from the relevant section of the jQuery documentation.

With all that said, let’s get stuck in! Rather than describing each option in the abstract, let’s start with an example:

// make the AJAX call

const myAjaxRequest = $.ajax({

url: 'https://www.bartbusschots.ie/utils/fakerWS/numberBetween', // REQUIRED

method: 'GET', // the HTTP method to use, defaults to GET

cache: false, // whether or not to allow caching, defaults to true

data: { // the form data to send to the server as a dictionary

arg1: $minTB.val(),

arg2: $maxTB.val()

},

dataType: 'text', // one of 'text', 'html', or 'json' (for now)

error: function(jqXHRObj, statusText, errorText){

// A callback executed on error.

// First arg is the jqXHR object representing the AJAX request.

// Second arg is the HTTP status string.

// Third arg is an error string.

window.alert(`AJAX call failed (status: ${statusText}) with error: ${errorText}`);

},

success: function(data, statusText, jqXHRObj){

// A callback executed on success.

// First arg is the data returned by the server.

// Second arg is the HTTP status string (almost always '200 OK').

// Third arg is the jqXHR object representing the AJAX request.

window.alert(`AJAX call succeeded (status: ${statusText}), returned:\n\n${data}`);

},

complete: function(jqXHRObj, statusText){

// A callback executed when the request is completed.

// This callback is executed on success and failure.

// This callback is executed after .success or .error

// First arg is the jqXHR object representing the AJAX request.

// Second arg is the HTTP status string.

// ...

}

}); // returns a jqXHR object representing the AJAX request

You can see this AJAX call in action by saving pbs76.html from the ZIP file to your local web server and accessing it over http://localhost…. Each time you click the button, the submit handler on the form will fire which will trigger the AJAX call above.

Note that https://www.bartbusschots.ie/utils/fakerWS is a web service I wrote that uses the open-source Faker PHP module to generate random data of various different kinds. If you’re curious how my web service works, I’ve open-sourced the code. You can get it on GitHub.

As you can see, the first few options can be easily matched to what we learned last time about HTTP requests. The first one that doesn’t is cache. This is a very convenient jQuery feature that adds an HTTP query parameter named _ with a random number as the value to the end of the URL. This forces the URL to be different each time, preventing all caching regardless of what your ISP may be doing to save bandwidth.

The data option allows you to specify name-value data pairs for sending to the server. When the method is GET, jQuery adds the data as query parameters. When the method is POST, it adds the data as form inputs.

The dataType option is a purely jQuery thing. It tells jQuery what preprocessing to apply to the returned data before calling the event handlers. Setting dataType to 'text' tells jQuery not to do any preprocessing and to just pass the data to the callbacks as a string. Setting the dataType to 'html' would cause jQuery to convert the string into a jQuery object using the $() function. Setting dataType to 'json' would cause jQuery to convert the value to a JavaScript object/array using JSON.parse(). These are useful conveniences.

Finally, error, success, and complete are callbacks which jQuery will execute when the HTTP request completes. If the request completes successfully, jQuery will execute success and then complete. If the request fails, jQuery will execute error and then complete.

A Challenge

Use either your solution to the previous challenge or my sample solution as your starting point (you’ll find a vision of my sample solution with the correct jQuery import in this instalment’s ZIP file as pbs76-challenge-startingPoint/index.html). If you’re using your own solution as your starting point, be sure to update the jQuery import line so it does not use the slim flavour!

Create a new file named contacts.tpl.txt and save it to the same folder as your HTML file (within your web server’s document root). Copy the contents of the <script> tag containing your Mustache template (not including the <script> tag itself) into this new file and save it. Then remove the <script> tag from your HTML file.

Update your JavaScript code so it loads the template from the separate file using $.ajax().

For bonus credit, can you do something similar with the <script> tag containing the JSON data? This is not as simple as it may seem because you’ll need to make two AJAX requests, both of which will need to succeed, before you can render your contact cards.

Final Thoughts

We’ll start the next instalment by looking at the complexities of juggling multiple AJAX calls that are interdependent on each other. What we’ll soon discover is that using callbacks for AJAX is hellish! At that stage we’ll be ready to learn about JavaScript promises, a very cool new feature added to the language with the release of ES7.