PBS 173 of X: Getting Started with Submodules (Git)

In the previous instalment we introduced the concept of nesting one or more Git repositories within another using Git Submodules. We explored some common use cases where sunmodules solve real-world problems, but we kept things conceptual and theoretical. In this instalment it’s time to get practical, to learn the actual Git commands for working with submodules, and we’ll do so using a simplified but common scenario.

Matching Podcast Episode

You can also Download the MP3

Read an unedited, auto-generated transcript with chapter marks: PBS_2024_11_23

Instalment Resources

- The instalment ZIP file — pbs173.zip

Git Submodules do not Imply Public Repositories

Since recording the first instalment there has been some confusion in the community conflating the concept of consuming one Git repository from within another and public Git repositories. Git can of course be used to work entirely in the open, as illustrated by its wide-spread adoption within the open source community. But Git can be used just as well to share resources within a closed, private community, like a business.

Like Git can be used both within public and private communities, so can Git submodules. To underline that point, all the following scenarios work just fine:

- A public repo can consume other public repos as submodules

- A private repo can consume other public repos as submodules

- A private repo can consume other private repos as submodules

- A private repo can consume a mix of public and private repos as submodules

When we start to use submodules within the PBS project we’ll be working entirely in the open, with all modules involved being public, but that’s just one way in which submodules can be used. To underline that point, our imagined scenario for this instalment’s examples will take the opposite approach — an entirely private community, an imaginary corporation, using purely private Git repos for purely internal collaboration with Git submodules.

A Note on Default Git Security Settings

For security reasons, modern versions of Git prevent the use of file paths as Git URLs under some circumstances. Git commands where a human directly enters the file path URL are permitted, but when one Git command triggers others, the triggered commands can’t use file path URLs.

When you run afoul of this security default you’ll get an error like this:

fatal: transport 'file' not allowed

In the real world, you’re most likely to be working with genuinely remote repositories over SSH or HTTPS, so you’re not likely to encounter this problem.

However, in order to keep our worked examples in this instalment self-contained, we need to use local folders to simulate remote repositories, so, we will encounter this problem.

The Git setting that controls whether or not file URLs are permitted is protocol.file.allow, and it has three possible values:

never— regardless of context, don’t allow file URLsuser— file URLs are allowed by direct user actions, but not indirectly, i.e. not within a triggered Git command. This is the default.always— file URLS can be used in any context, i.e. for direct user actions, and, within any triggered Git commands.

A Per-Command Exemption (Used in our Examples)

Git’s security defaults were added for good reasons, so we want to make the minimal possible exception to facilitate our examples. Rather than setting the configuration globally, we’ll set protocol.file.allow to always (direct and triggered commands) on a per-command basis, and only when we need to. This means that the moment our command and its triggered commands finish, the exception will disappear.

The mechanism for doing this is Git’s -c option for passing a value for any configuration variable at run time. The option takes the form -c NAME_OF_SETTING=VALUE. To enable file URLs in all contexts we need to add the following to any Git commands that trigger other Git commands:

-c protocol.file.allow=always

A Permanent Exemption (Only use if you Regularly use File Path URLs)

It’s possible that you want to use submodules in an environment where file-based URLs are the norm. The only realistic example I can think of would be an organisation that hosts its Git repositories on a shared folder that gets mapped as a drive on developer PCs. In such a scenario, you probably want to make a permanent exception, which you can do by updating Git’s configuration for the current user with the command

git config --globalcommand:# WARNING - THIS ADDS A PERMANENT SECURITY EXCEPTION git config --global protocol.file.allow alwaysBut remember, this is not recommended!

A Note on Terminology

Remember — submodules are nested repositories, so each submodule folder is a Git repository in its own right.

This means is a real danger of confusion between the all the different repositories at play.

To illustrate the scale of the possible confusion, consider a repository that has two submodules. You obviously have at least three repos, the three local ones — the primary repo with the two submodules, and each submodule folder within it. But Git submodules are, by definition, clones of a source repository, so for every submodule there are actually two Git repos in play — the local clone in its folder within your primary repository, and the remote they are linked to. That brings us up to five, but wait, there’s more! The primary repo that contains the submodules is itself likely to be cloned from a remote, so now you have six repos!

To try keep things clear I’ll refer to the primary local repository which contains the submodules as the outer repo. I’ll refer to the local copies of the consumed remote repositories as inner repos or submodules.

Our Overall Scenario — A Small Web App Business

To explore Git submodules we’re going to pretend to be a fledgeling business that builds web apps, all of which share the company’s branding.

To keep things consistent across current and future apps, the branding is versioned in its own private Git repository named pbscorp-brand. Each web app has its own repo, with names like pbscorp-app1. The app repos consume the brand repo as a Git submodule.

To play along, start by downloading the instalment ZIP file, extracting it, opening a terminal in the extracted folder, and executing the initialisation script initPBS173Demo.sh with the commands:

chmod +x *.sh; ./initPBS173Demo.sh

This script does the following:

- Creates parent folders to simulate different different computers:

remote-reposto represent the company’s GIT serverpc-app1Devto represent the PC of a newly hired developer who’s just been assigned to app 1pc-app2Devto represent the PC of a developer tasked with creating the brand-new app 2pc-brandDesignerto represent the PC of a designer tasked with maintaining the brand

- Expands the bundled repos

pbscorp-brand.bundleandpbscorp-app1.bundleinto the bare repositoriespbscorp-brand.git&pbscorp-app1.gitin theremote-reposfolder (the simulated corporate Git server) - Creates a complete empty bare repository

pbscorps-app2.gitin theremote-reposfolder (for use in scenario 2) - Clones the

pbscorp-brand.gitrepo into thepc-brandDesignerfolder (for use in scenario 3a)

Finally, just a reminder that Git repositories intended for use as remotes must be bare to prevent warnings and possible corruption. They are folders, and by convention, named with a .git extension. A bare repo is simply a repo without a working copy, so no changes can be made within that repo, they can only be pushed to it. For more on remotes and bare repos see instalment 113.

Scenario 1 — Cloning a Repo with Submodules (New Developer Joins App 1 Team)

Your first introduction to submodules will likely be cloning an existing repository that makes use of them, maybe in work, or maybe from some open source project. Without a basic introduction to submodules, this can be a very frustrating experience! Why? Because at first glance, it will appear the code in the repository is broken! But don’t worry, just a few simple Git commands will get things running smoothly for you.

In our imagined scenario we are a developer who has just joined the team working on App 1, so we want to clone it to our computer. If you’d like to play along, please change into the pc-app1Dev folder.

In the real world, the URL for the repository we wish to clone which happens to use submodules will most likely be a genuinely remote repository that we connect to over SSH or HTTPS. But in our example, we’ll use a simple relative file path as the URL, specifically, we’ll use ../remote-repos/pbscorp-app1.git.

We can clone the repo as normal with the command (remember to make sure you are in the pc-app1Dev folder):

git clone ../remote-repos/pbscorp-app1.git

This command will appear to clone the repository without issue, and at first glance, all seems well. When you look inside the repo you’ve just cloned, you’ll see a file named index.html, and a folder named brand. But, if you open index.html in your favourite browser you might notice that the app looks like an un-styled Bootstrap 5 app, and if you open the developer console you’ll see an error to the effect that brand/style.css could not be found. This is our first clue that our submodule has not been initialised.

Before we resolve our issue, let’s explore this repo a little more so we can learn how to tell if we have a clone with uninitialised submodules. Start by changing into the newly cloned repo with the command:

cd pbscorp-app1

We might imagine running git status to see the state of the repo would show us we have a problem, but it will not, it simply outputs:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

While this wasn’t illuminating, there are two ways we can tell our newly cloned repo uses submodules. First, at a simple file system level, any repo that uses submodules will contain a file named .gitmodules. If you view the contents of this file you’ll see that it contains the mappings between the folder names and the URLs for all the submodules that have been added to the outer repo. In our repo we can see by running the command:

cat .gitmodules

In our case, this outputs the details for just one submodule:

[submodule "brand"]

path = brand

url = ../../remote-repos/pbscorp-brand.git

We can see that there is a submodule, and we can see the remote URL it should be cloned from, and the local folder it should be cloned into. To learn which remote commit our currently checked-out branch of the outer repo specifies for the submodule, issue the command:

git submodule status

In our case, this shows:

-4e4c1243d73d16db9c331f88eab907cc8a4b61eb brand

This tells us three things:

- That the

brandfolder is a submodule, (because thegit submodule statuscommand only lists submodules) - The ID of the remote commit that should be checked out in the submodules’s local folder.

- The

-before the commit tells us that it hasn’t yet been pulled

OK, so now that we know we have a submodule, how do we get the brand folder populated?

The first step is to tell Git to integrate the submodules specified in .gitmodules into its database in the .git folder. Use the command:

git submodule init

This will show Git registering one submodule, and resolving the URL to a full path. For me, the output was:

Submodule 'brand' (/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/From GitHub/programming-by-stealth/instalmentResources/pbs173/pc-app1Dev/../remote-repos/pbscorp-brand) registered for path 'brand'

Note that you only need to initialise submodules in two circumstances:

- When you clone the repo initially

- When you pull a change that adds a new submodule to the outer repo

You might imagine initialising the submodule would clone it into the brand folder, but alas, no, the folder is still empty. To actually check out the correct commit from the submodule’s remote repo into the folder you need to run the command:

git submodule update

This will check the currently checked out commit in each submodule against the outer branch’s current saved state for the submodule, and perform any needed checkouts.

When working with truly remote repos this will just work, but as explained earlier, for security reasons, this command will fail with our local directories. We need to explicitly tell Git we are OK with file path URLs for our submodules by adding the configuration option described above, so for us, the command becomes:

git -c protocol.file.allow=always submodule update

Now you should see the submodule being cloned and the appropriate commit checked out into the brand folder. For me the output was:

Cloning into '/Users/bart/Documents/Temp/From GitHub/programming-by-stealth/instalmentResources/pbs173/pc-app1Dev/pbscorp-app1/brand'...

done.

Submodule path 'brand': checked out '4e4c1243d73d16db9c331f88eab907cc8a4b61eb'

Note the ID of the checked out commit matches the output from git submodule status command we ran earlier.

Reload index.html in your browser and you should see the app adopt its corporate branding (and the console error will be gone).

Scenario 2 — Adding a Submodule to a Repo (Starting App 2)

We’re now going to pretend to be a different developer, one who’s responsible for starting App 2. The PBS Corp sysadmins have done their bit and created an empty git repository named pbscorp-app2 on our simulated Git server (remote-repos/pbscorp-app2.git), so it’s waiting there to be coned and filled with code!

To play along, start by changing into the folder representing this developer’s PC — pc-app2Dev.

From that folder, start by cloning the (empty) remote repo for App 2:

git clone ../remote-repos/pbscorp-app2.git

Change directory into the newly cloned local copy of the repo:

cd pbscorp-app2

Create an index.html with the initial code for the app from the file pbscorp-app2-index-1.html in the instalment resources ZIP:

cp ../../pbscorp-app2-index-1.html ./index.html

Commit this initial version and push it to the ‘remote’ repo on the pretend corporate Git server:

git add index.html

git commit -m "Feat: initial implementation"

git push

If you open index.html in your browser you’ll see that we now have a working silly little web app counting down to Christmas. Apart from the baseline Boostrap 5 styles, it’s completely un-styled, so it’s missing the PBS Corp brand. Let’s remedy that by adding it as a submodule!

Our company brand is available in the Git repo pbscorp-brand, and we’d like to include it in our repo in a folder simply named brand.

The git command to add a submodule is git submodule add, and it requires at least one argument — the URL for the remote repo. By default the base name of the remote repostitory (the last part of the URL with the .git extension removed) is used as the folder name, but you can override that with an optional second argument. That means the basic form of the command is:

git submodule add REMOTE_REPO_URL [LOCAL_FOLDER_PATH]

Before we do anything, note that there is no file in our repo named .gitmodules, and the git submodule command returns nothing:

cat .gitmodules

# cat: .gitmodules: No such file or directory

git submodule

# returns no output at all

OK, let’s now add the brand to our repo as a submodule.

For our purposeses the URL to our ‘remote’ repo is ../../remote-repos/pbscorp-brand.git, so the default folder name within our repo would be pbscorp-brand. Since we want the repo cloned into in a folder named brand instead, we’ll need to supply the optional second argument:

git submodule add ../../remote-repos/pbscorp-brand.git brand

This will fail purely because we are using a file path as a URL without explicitly telling Git that we’re OK with that, so, let’s add the Git configuration variable to enable file paths and try again:

git -c protocol.file.allow=always submodule add ../../remote-repos/pbscorp-brand.git brand

You’ll see that this clones the remote repo into the brand folder. I’d like to draw your attention to a few things:

-

There is now a file named

.gitmodulesin the root of the repo, and it maps our remote URL to the folderbrand:cat .gitmodules # [submodule "brand"] # path = brand # url = ../../remote-repos/pbscorp-brand.git -

The

git submodulecommand now lists one submodule:git submodule # 4e4c1243d73d16db9c331f88eab907cc8a4b61eb brand (heads/main)Note that it shows the ID of the currently checked-out commit, then the name of the folder, then the remote branch checked out.

-

The submodule has been cloned, so the stylesheet is there:

ls brand # style.css

By adding a submodule, we have made a change to the outer pbscorp-app2 repo, but we have not committed it yet. Before we do any more, let’s get the state of our repo with git status:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: .gitmodules

new file: brand

I’d like to draw your attention to three things:

- The changes were automatially staged, we did not need to use

git addto stage them. - The

.gitmodulesfile is versioned in Git just like the.gitignorefile is. - The entire submodule is presented as a single ‘file’ with the folder’s name.

We can now enable the corporate brand by editing index.html to include the stylesheet brand/style.css. The line to add is simply:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="./brand/style.css">

But you’ll find the full updated file in the instalment zip as pbscorp-app2-index-2.html, and you can copy it over your current file with:

cp ../../pbscorp-app2-index-2.html ./index.html

Now, when we open index.html in our browser we see the corporate brand has been applied.

If we do another git status can can now see that we have three changes waiting to be committed:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: .gitmodules

new file: brand

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: index.html

So, let’s commit and push these changes:

git commit -am 'Feat: incorporate the corporate brand using a submodule'

git push

Scenario 3 — Pulling Submodule Changes (Updating the Brand)

Next, let’s look at how we can pull changes into a Git submodule by walking through a brand update. We’ll start the process by acting as the brand designer, then we’ll change hats and become the developer of app 1, and finally, we’ll change hats again to become the developer of app 2.

why are we apparently doing the same thing twice? Are we updating App 2 just for repetition? No, we’re doing it twice, because there are two ways to do it.

The Git docs on submodules give instructions for what I think of as the outside-in approach — you issue all your commands from the outer repo, not from the inner repos. This works well if you want to update all your submodules at once.

The other way to do it is from the inside-out, that is to say, we enter into each submodule, and we make use of the fact that is is just a regular Git repository that happens to be nested in an outer repository, to interact with it using traditional fetch, push, and pull commands. In my real-world experience, I want to update each submodule seperately, so I always work this way because it involves learning zero new Git commands 🙂

Scenario 3a — The Brand Designer Updates the Brand

To play the part of the brand designer, change into the pc-brandDesigner folder. In here you’ll find a freshly checked-out copy of the pbscorp-brand repository, so change into that folder (cd pbscorp-brand).

Note that from our point of view as the brand developer we are working on a regular Git repository. The fact that other repositories will consume this repository as a submodule makes no difference to how we interact with our copy of the repository.

Verify that the repository is clean with a quick git status.

We want to make a change to the brand so that alternate level headings are in different colours. At the moment, all six HTML header tags render in dark blue, we’d like to keep doing that for <h1>, <h3> & <h5>, but to start rendering <h2>, <h4> & <h6> in dark green.

The updated style sheet is saved in the base of the installment ZIP as pbscorp-brand-style-1.css, you can copy it over the current style with the command:

cp ../../pbscorp-brand-style-1.css ./style.css

Verify that the change has indeed been made with another git status, it should show that there is one file changed:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: style.css

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can now commit and push our change:

git commit -am 'Feat: alternate heading colours'

git push

Scenario 3b — The App 1 Developer Incorporates the Updated Brand (Outside-in Method)

To play the part of the app 1 developer, change into the pc-app1Dev folder. In this folder, we’ll find the copy of the app we checked out in scenario 1, with its submodule for the brand initiated. Change into that repository (cd pbscorp-app1).

You might be wondering how can we, as a developer of App 1, can tell that there’s a change available for us to pull in the brand submodule?

You might assume a regular git status would show the possible changes, but it will not. It simply outputs:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

This is a true reflection of the status of our copy of the outer pbscorp-app1 repo, but it’s completely ignoring the remote repos linked into our repo as submodules.

To instruct Git to recursively fetch all possible changes, both for the outer repo and for all submodules, use the command:

git fetch --recurse-submodules

In effect, this triggers a git fetch within each submodule, and it at least lets us quickly see if any of the remote repos for our submodules have changed in any way. In our case we can see that the brand submodule has remote changes we can choose to pull:

Fetching submodule brand

From /Users/bart/Documents/Temp/From GitHub/programming-by-stealth/instalmentResources/pbs173/pc-app1Dev/../remote-repos/pbscorp-brand

4e4c124..9c84c1c main -> origin/main

Remember that git fetch only updates the local cache of a remote repo, it does not actually merge the changes into our local repo.

To actually merge in the remote changes we need to use the git submodule update --remote command, but because we’re using file path URLs, and because this is a Git command the triggers other Git commands, we’ll get an error if we don’t add our config to explicitly allow that, so for us the command becomes:

git -c protocol.file.allow=always submodule update --remote

The output shows brand being updated to a new commit:

Submodule path 'brand': checked out '9c84c1c83fd771642d432118808cbfb4571d8355'

If we now open App 1’s index.html in our browser we’ll see that the headings are no longer all blue, so we have successfully updated our copy of the brand from the remote repo.

We have now updated our brand submodule to a new commit, but we have not commited this change of checked out immer commit in the outer repo (pbscorp-app1). We can see that this is the case by running a git status:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: brand (new commits)

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Remember that what Git is storing in it’s database for brand is:

- That it is a submodule

- Which remote it is linked to

- Which commit is checked out in the submodule’s folder

In effect, the entire state of a submodule is folder is distilled down into the ID of a single commit. Whether it contains one file or a million files, the entire contents of a submodule folder gets saved in the outer repo as a single commit ID!

So, from the outer repo’s POV, changing the checked out commit in a submodule is no different to changing a line of text in a versioned file — it’s a change that needs to be committed.

So, let’s commit and push that change in the outer repo:

git commit -am "Feat: update brand"

git push

Scenario 3c — The App 2 Developer Incorporates the Updated Brand (Inside-out Method)

As we said before, we could incporporate the brand change into App 2 in just the same we wd did it for App 1, but instead, let’s learn the other approach you can take. Let’s work with our submodule without using a single command we didn’t know before this instalment, we’re just going to use git fetch (optional), git status, git pull, git commit, and git push to update the Brand used by App 2. In other words, we’re going to treat both the inner and outer repos as what they are, regular Git repos!

To work with a submodule like the regular Git repo it is, simply change into it!

If you want to play along, start by changing into the folder pc-app2Dev/pbscorp-app2/brand.

Let’s get the lay of the land first by running a simple git status:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

As you can see, the command behaves completely normally. But, you may complain, why am I not seeing the remote changed ready to be pulled? Simple — we haven’t updated our local cache of the remote repo yet, so let’s do that in the normal way:

git fetch

(Note: if you use GUIs a lot, you’ve probably forgotten that you always have to do this to see remote changes because most GUIs fetch automatically each time you interact with them!)

If you watch the output of the fetch you’ll notice a new commit on origin/main, but you don’t have to pay such close attention and catch this onformation scrolling by. Now that you’ve fetched you can see the new remote commit in the output of a git status:

On branch main

Your branch is behind 'origin/main' by 1 commit, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Oh look, we’re one commit behind our remote! To incorporate the change we just pull as normal:

git pull

(Reminder: git pull implicitly does a git fetch first, so to blindly pull in all changes without seeing the details first you can skip the git fetch and just do a git pull right off the bat).

We have now incporporated the changes from the remote brand repo into the brand folder. If we change back up the outer repo with a simple cd .. the all our commands will again be addressing the outer repo, not the submodule repo, so we can see that we now have a change to commit here too, because the checked out commit in the submodule has changed. To see this, just run another git status:

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: brand (new commits)

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

We can now commit and push the brand update just like we did in scenario 3b:

git commit -am "Feat: update brand"

git push

A Note on Git GUIs — Most Show Submodules

We’ve learned that if you’re working from the command line, you will know the repo you’re working on has submodules if it contains a file named .gitmodules. In .gitmodules you’ll find information about the submodules.

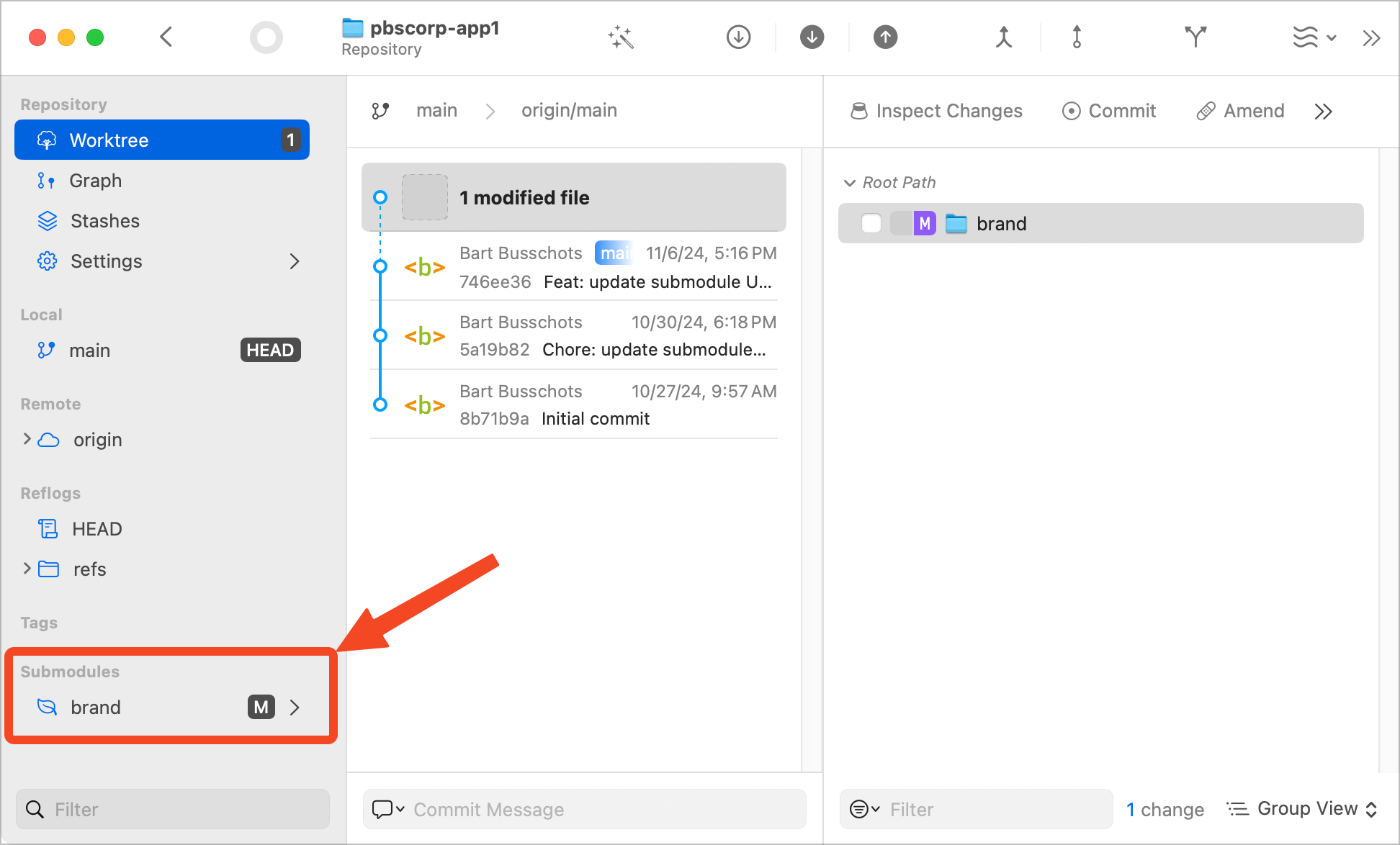

But if you’re working with a Git GUI - how would you know that if your repo has submodules? If you look closely you’ll notice, perhaps in a left sidebar, that there’s a folder called Submodules. As an example, in Gitfox you’ll see the word submodules and upon hovering you’ll get a chevron to show the name of any submodules with a nice little leaf icon next to it.

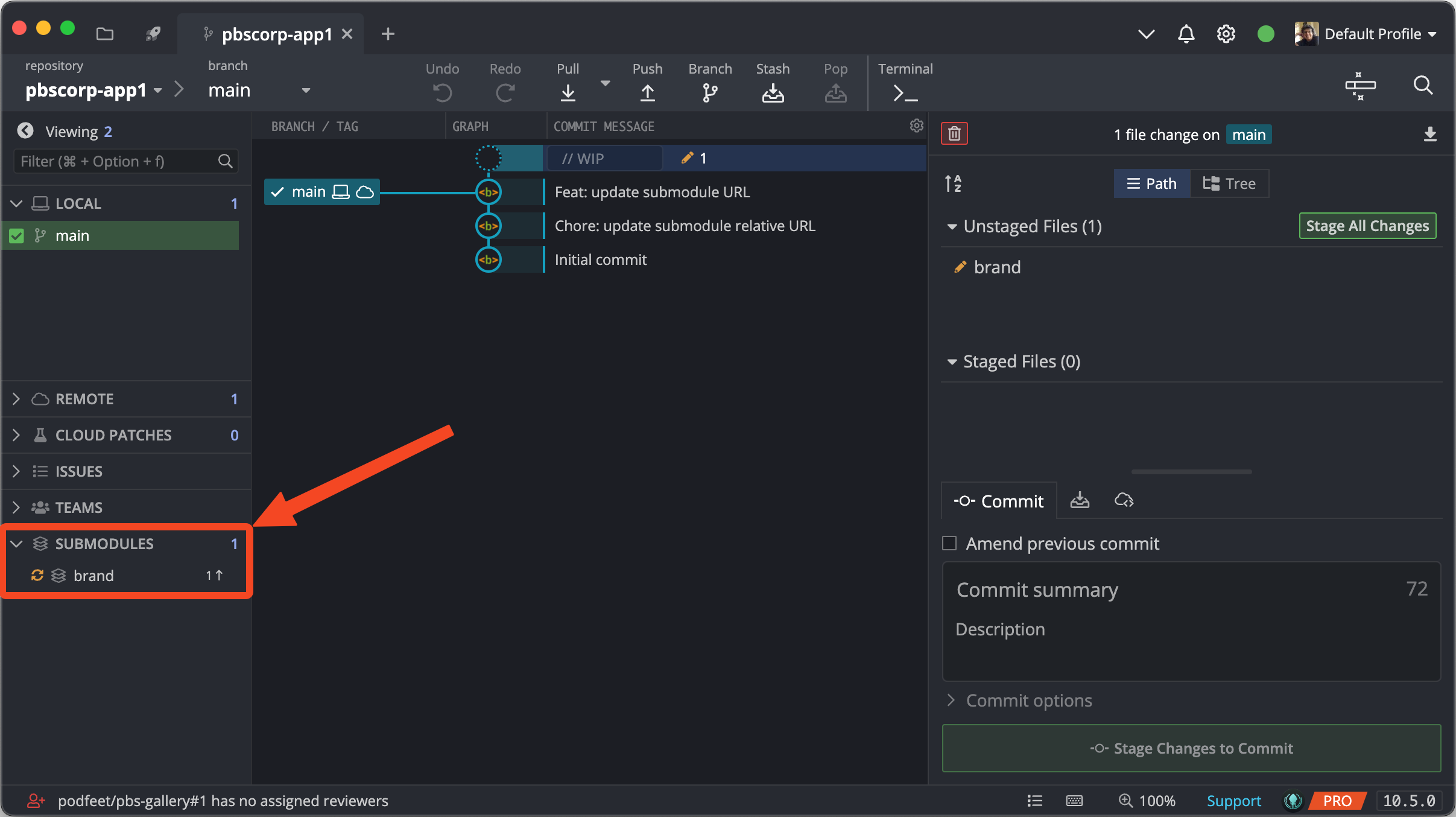

In GitKraken, you’ll also see submodules in the left sidebar with a chevron to open. GitKraken also puts a number next to it to tell you how many submodules you’ll find inside.

Final Thoughts

We’ve arrived at a natural break point for our exploration of Git submodules, but there is more to come in the next instalment. To this point, changes have flowed purely one way — with each app developer only consuming changes to the brand via a submodule. No changes have been contributed in the other direction. Pushing changes upstream from a submodule back to the remote repository it’s linked to will be where we start the next instalment. Then, we’ll move on to the last concept we’ll tackle in this basic exploration of submodules — dealing with branches.